John Hutchcocks started work at Accles & Pollocks as an apprentice engineer and draughtsman in September 1954. He eventually became a Development Engineer overseeing tube production in the sports department.

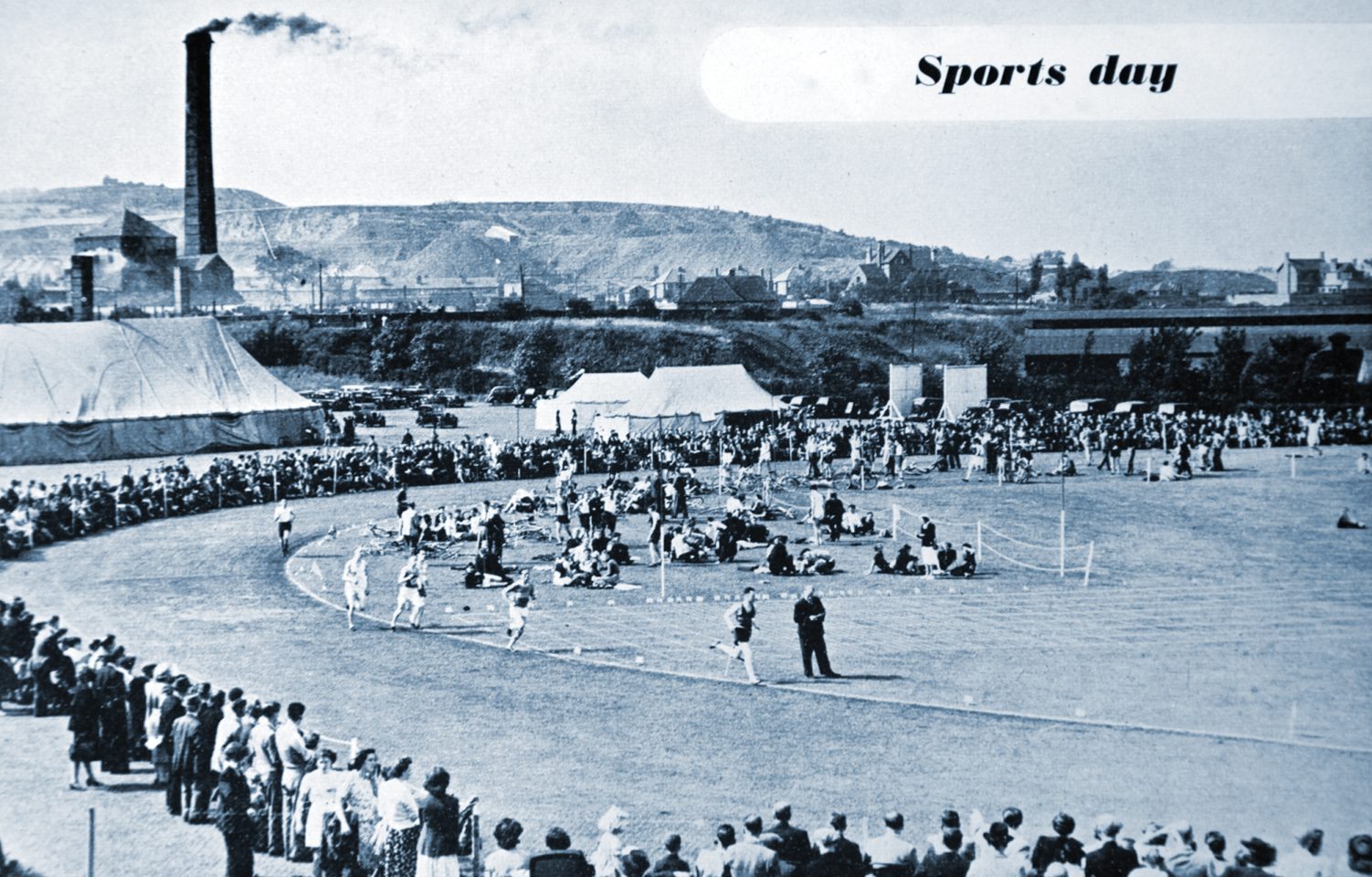

“When I first joined the company my interview was with a guy called Jim Spencer, who was an ex-Albion player. To get to Jim, who was the Personnel man, you walked through the Safety Office where I found Cyril Teague, who ran the Fire Service and the Boys Club - for boys who didn’t have a lot of money, they’d get taken away on a holiday in the works shutdown. So I went into see Mr Spencer, said my piece and all the rest of it. I then started to come out through Cyril’s office and he immediately looks up and said, ‘What position does he play, Jim? We’re short of goalkeepers this year.’ It just happened to be that I played in goal, so I got the job, no question about it.

I was told: ‘If you’re interested in playing football, turn up next Saturday at Birchley.’ That’s where the M5 junction is these days. There was a nice big field. I turned up. They’ d already started the first half. At half-time they gave me a trial. They put me in the second team. It was something to do, more people you got to know. In later life, they became useful these guys because you used to play football with them. You went to them with a problem and they’d solve it for you. You got to know names, you got to know faces.

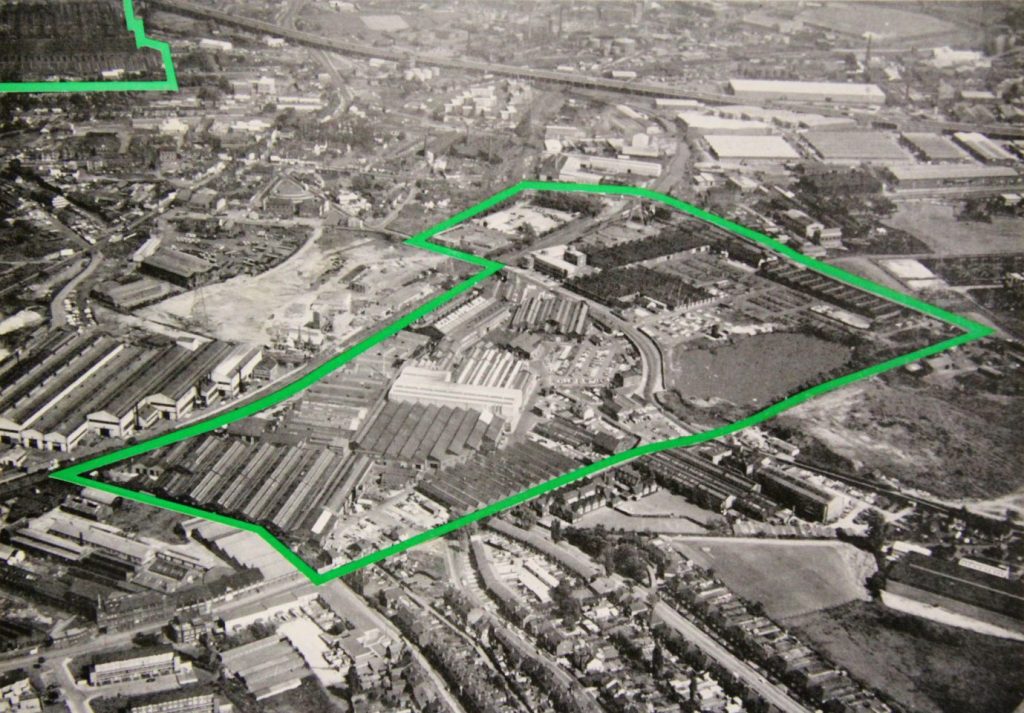

At the same time I started, there were 200 other apprentices. The company was 5000 strong, spread over two factories at Paddock Works and Broadwell and there were offshoots; things they had taken away from Accles & Pollock and started as new companies. PEL furniture, that was a part of the combine in those days. About nine months after I started work, we moved office. We were upstairs in an old office block, cold in winter, too hot in the summer and if we made too much of a racket the girls in the wages office complained, so we got told off. Strangely enough just before I started, we had a new product in the development office. It was the sort of thing we did there; they had produced a pogo stick which had got two steps and a spring inside and we used it to jump up and down. So when the plaster started falling off the wages office ceiling the girls complained bitterly and their boss came banging on the door, telling us to belt up.

I spent a couple of years in the office being shown how to draw proper and getting told off if I didn’t do it right. I’d got too gentle a touch at college, because there nothing ever had to be turned into a blueprint, but at work you needed a good sharp line for it to print. I found out all about that. I found out you don’t have to do three dimensions or three views for a piece of tube, because it’s the same one side as the other when you look at it. There’s not a lot you can do about it. If you have to do a bend, all right, you have to do a few more details on that. They found out what you were good at and that’s where they directed you.

They found I couldn’t spell very well, so I was taught how to spell one or words that were a bit necessary and to talk properly. I had to find out how to talk in the Black Country language. Although I was born In West Bromwich, my father was from Smethwick, so I’d got a West Bromwich-Smethwick accent. Most of the people that worked at Accles and Pollock in those days came from the immediate vicinity, or the other side of the Wolverhampton New Road. So I was rather a rarity coming from West Bromwich and being employed there.

We were allowed one day a week off, to do college and we did night school for two nights a week. I got through the year, then did the Ordinary National exam, and I by this point was going around the company, getting a good grounding in all the work. You learned how to swear, not that I didn’t know before, but they told you who to swear at and who not to swear at, put it that way.

I went into the Experimental Tool Room, where they called a spade a big shovel. I never got sent for a left-handed spanner, down to the stores or anything like that. There was none of that, they just got on with the job. I soon discovered in my tour around the company doing various things, everybody thought that they were the bee’s knees. ‘We are the best tube company in the world. This is Accles & Pollock. If anyone tells you differently they are wrong. We are the best.’ That carried on through the whole of my apprenticeship and I still feel that now. That was the sort attitude with everything we did - if somebody can do something, we can do it better.

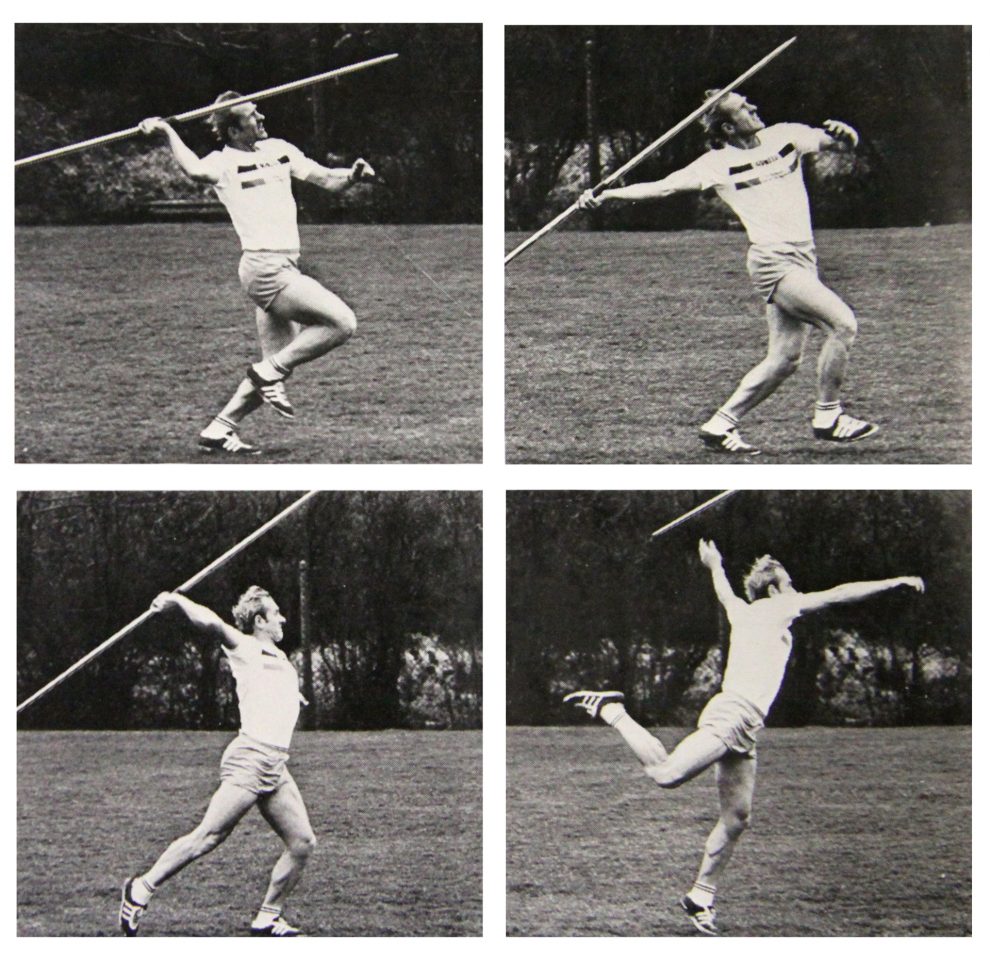

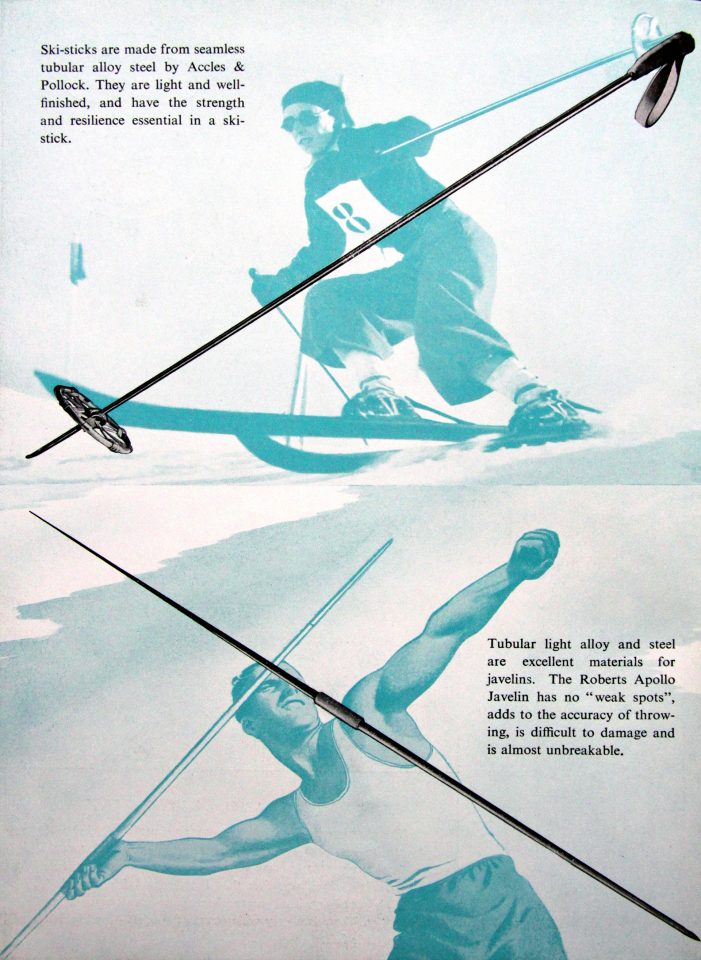

You know the basket that goes round a ski stick to stop it going too far in the snow? That was the first thing I ever drew; it was a piece of metal braised on or silver soldered onto the end of the ski stick, about six inches up. We actually had an order from Norway or Sweden for thousands of these things. At Accles, we also had orders for fishing rods, softball bats, snooker cues. We did archery bows; we had the Ladies World Champion working in the company. We had a world record for javelins. When my old boss in production had about three or four years to go before retirement, they stuck him in the corner and he played with javelins and came up with a world record beating design. We also did the pole vault beams they jump over - those were always getting bent and broken so I had to find a way to stop the wear and tear.

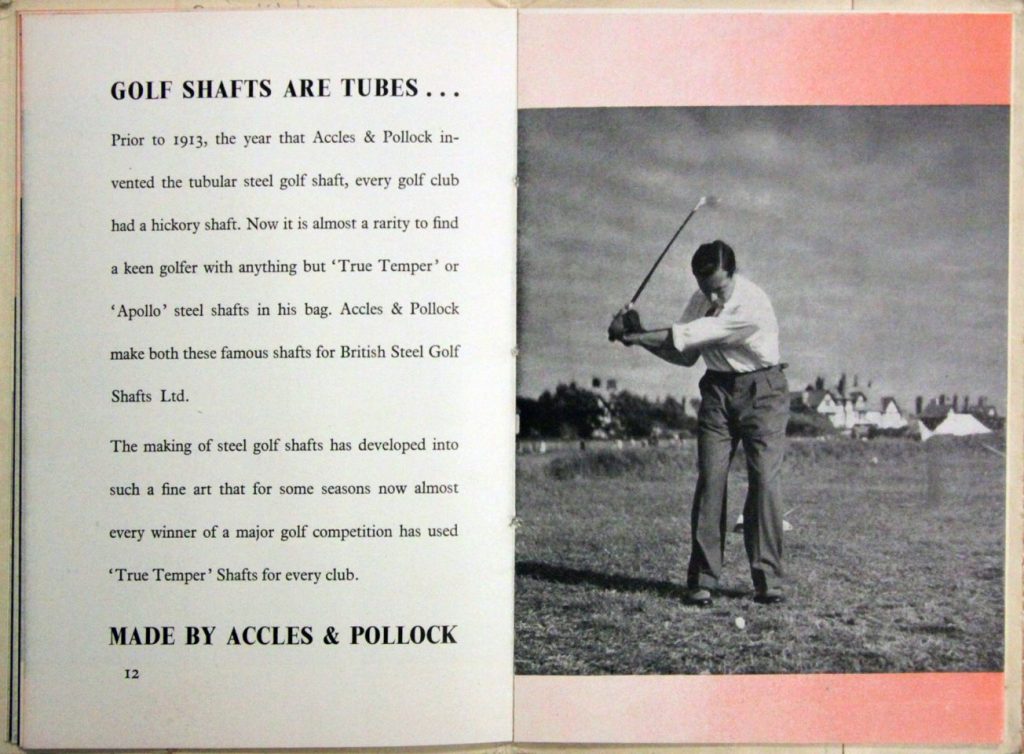

I worked with extended surface tubes; if you take a piece of tube, which has a screw thread on the outside, it transfers heat much faster into the centre. They were used in heat exchangers, condensers, cooling equipment. I had a little spell in Production Control, when we were starting to first use computers. Then I went back onto sports equipment, specifically golf shaft design, which I did for some 15 years before retiring.

It took me about a fortnight to design a golf shaft – it was all big graphs and lots of calculations. Then if you were lucky and hadn’t made a mistake in the first line you’d get something that would bend by the correct amount. If it didn’t bend by the correct the right amount, you went through the whole blessed thing again and found four lines down you’d done something right stupid and you needed change what you were thinking. We started to do all this on computer. The first programme we had for this was on an 8k Wang, with a 9-inch television screen, a beautiful little thing, and underneath it - to make it work - we’d got an audio-tape which held the programme. We didn’t have any memory on the blessed thing. We had a keyboard. We didn’t have a printer at first, we kept notes. We didn’t even have it at the company in Oldbury. I had to go over to Aldridge to the airport, which was our group’s engineering department. We had to do a lot of tests to get the programme right to make these golf shafts. It was my job as a designer to make that golf shaft bend by the correct amount. I enjoyed doing that. On occasions I looked forward to going to work.

Golfers can be a funny bunch. One would want something that was heavy as a stone, another would want something completely different. A golf shaft is made from a piece of plain tube, but the tube isn’t the same thickness as one end as the other end. The bit that goes into the head of the blub has to be bigger and stronger, as it has more stress when it hits the ball. So that end has to be stiffened up, by making a tapered wall section along the tube. You can change the length of the reinforcement. You take the tube, put it on a step-forming machine, pushing it through a series of dies, watching it doesn’t move sideways and buckle up.

Once the tube was drawn and tapered, it had to be heat treated in a furnace to be hardened. It was called austempering, exactly the same treatment that you would give a clock spring, before we had these electronic gadgets we wear on our wrists nowadays. You’d take the take tube up to 850-900 degrees and it was dropped into a molten salt at 300 degrees, and held there for about half an hour. After you take it out, you have to polish it, make it nice and shiny and then put on the chromium plate on, then get the hydrogen out of the plate before it starts attacks the steel - that’s done with another little cooking operation. Then you print the name on and send it out to the customer after all the girls have had a look at it to check there’s no dents or scratches or tears. We used to send out 250,000 a week on average. Don’t ask me who had them all!”