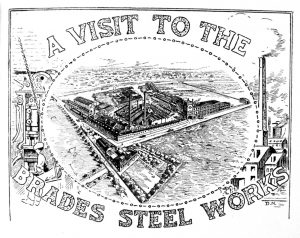

Elihu Burritt, an American consul in Birmingham, has already been this way, mostly on foot, in order to fulfil his duty to report on trade in the district and ‘other facts bearing upon the productive capacities, industrial character and natural resources of the communities embraced in their consulates.’ His book - ‘Walks in the Black Country and its Green Borderland’ - is published in 1868.

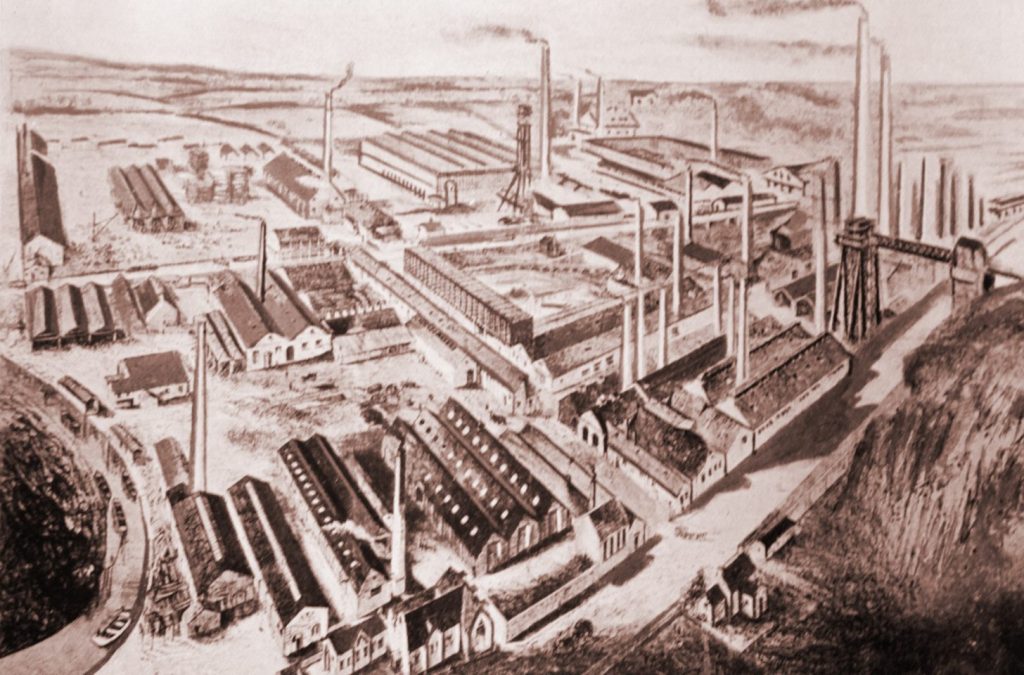

Here he finds a ‘district of fire and smoke and artificial thunder and lightning’ and a ‘black forest of forge and furnace chimneys.’ He visits the Brades Iron and Steel Works. He is mightily impressed by their trowels and hoes, as well as the prodigious implements they make for agricultural purposes. Of the work there he writes:

‘To speak of white heat, or the heat of molten gold or silver would be like comparing the flame of a yellow tallow candle with magnesian light. As the stalwart men, naked to their waists, remove the cover from the pot and pour the fluid into flasks for ingots, the brightness is almost blinding even to one standing at the distance of several paces. As the whizzing steam runs into the mould, it emits a sparkling spray dashed with rainbow tints from various ignited gases.’

The journeyman Bohemian writers also recorded vivid impressions of this area in their notebooks:

The journeyman Bohemian writers also recorded vivid impressions of this area in their notebooks:

‘Passing the outskirts of Birmingham, where the tall factory chimneys rise at intervals on either side of the railway line, leaving the charming suburb of Edgbaston and the manufactories of Soho and Smethwick, the approach to Oldbury is marked by a heavy pall of smoke which, hanging over the whole tract of the country, shrouds nature in a dun eclipse. Amidst an undefinable labyrinth of pit banks and hillocks, mounds of cinder, craggy masses of clinker, often lighted by a lurid glare into strange and fitful shape, rise the more regular forms of innumerable shafts, kilns, tall, pyramidal blast-furnaces, and strange uncouth machinery. Crowded together amidst this volcanic waste, as though separated for ever from the life of villages and country homesteads, lie the pitbanks, the collieries, the forges, the works for iron and steel and gas, tin and tar, copper, oil, and lead, the soaperies, the distilleries, the potteries, and, as it seems, a hundred others, for supplying the world with material which has become a second nature wrung from the necessities of the first. Here, amidst din and clangour, rises the hot breath of a thousand forges, the heavy vapour of brick and lime-kilns, the black and choking smoke of mighty fires, all mingling in one great, black, boding cloud which broods immovable above the earth.’

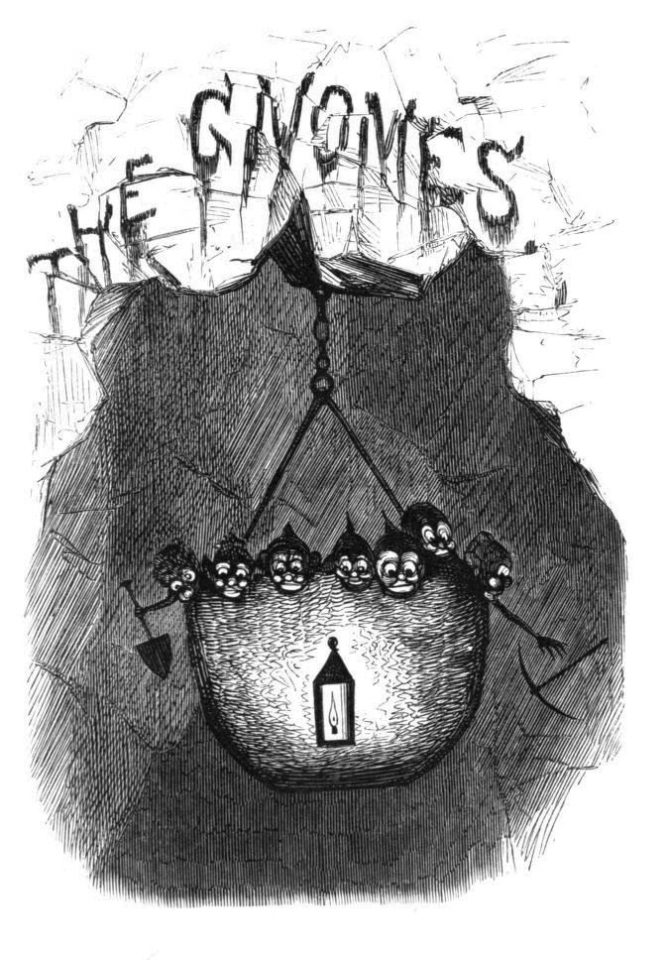

They refer amongst themselves (and share this thought later with their reading public) to ‘a charming little book’ for children called ‘Fairy Tales of Science,’ recently written by one of their number. They feel they have now encountered such a magical place, a philosopher’s zone of alchemy ‘where Fancy may revel and Imagination soar’, as they step down from the train at Bromford Lane, suddenly arriving ‘at the outskirts leading to a kingdom of some eminently scientific gnome; for, continuing our journey to the realms of chemical manufacture, we pass between glittering cliffs which change their hues as we proceed, from pearl white to shimmering sea-green - see masses of green stalactites heaped here and there - stop before the sheen of crystals - walk upon snow-pure sands - gaze, wonderingly, at hillocks of red, and brown, and black, and brilliant colours, amidst which rise two gigantic chimneys and a score of towers.’

They refer amongst themselves (and share this thought later with their reading public) to ‘a charming little book’ for children called ‘Fairy Tales of Science,’ recently written by one of their number. They feel they have now encountered such a magical place, a philosopher’s zone of alchemy ‘where Fancy may revel and Imagination soar’, as they step down from the train at Bromford Lane, suddenly arriving ‘at the outskirts leading to a kingdom of some eminently scientific gnome; for, continuing our journey to the realms of chemical manufacture, we pass between glittering cliffs which change their hues as we proceed, from pearl white to shimmering sea-green - see masses of green stalactites heaped here and there - stop before the sheen of crystals - walk upon snow-pure sands - gaze, wonderingly, at hillocks of red, and brown, and black, and brilliant colours, amidst which rise two gigantic chimneys and a score of towers.’

This landscape, however, cannot be said to be pretty. While there are still some patches of green, this is an area of mine workings, factories and canals, spoil heaps and ever deepening marl holes. There are no picturesque ruins. Decades later, in 1915, Staffordshire writer and historian F.W. Hackwood writes in ‘Oldbury Round and About’:

This landscape, however, cannot be said to be pretty. While there are still some patches of green, this is an area of mine workings, factories and canals, spoil heaps and ever deepening marl holes. There are no picturesque ruins. Decades later, in 1915, Staffordshire writer and historian F.W. Hackwood writes in ‘Oldbury Round and About’:

‘Corroding gases emitted from chemical works in the heart of the town so completed the blight that even the grass and the hardiest of plants failed not to succumb. Not by incessant labour could Oldbury housewives keep fire irons or other utensils of bright steel in any desirable condition of cleanliness; metal tarnished in a single night and in the process of time faded away as they had been petals of a fading flower.’

At this time the town is heavily involved in production of armaments. Albright & Wilson manufacture phosphorus bombs, Chance Brothers' Alkali Works produce TNT in a new government factory erected for the purpose. Most of the tanks used in the First World War are made at the Oldbury Carriage Works. In 1916, under conditions of great secrecy, Oldbury Carriage Works began production of a new weapon of war, the tank, producing the first 1000. Their wheels, frames, ironwork, and other components came from local factories and expertise in the Black Country. Even the testing was done in Oldbury. In 1918, they produced over 2000 tanks at short notice for use in the 100 Days Offensive, which brings the Greta War to an end.

The driving force for the use of such vehicles came from the Royal Navy, many of whom were consequently stationed in the Black Country, involved in both the design and testing of the weapons produced. The Navy were also responsible for the transportation, and the delivery of each tank to the war zone - hence their initial designation as ‘landships’. Many of these vehicles produced in Oldbury were to be deployed after the Armistice, in the occupied countries or in continuing zones of conflict, with British troops in action as far afield as Mesopotamia, Murmansk and the Caucasus.

John and Joan Beach

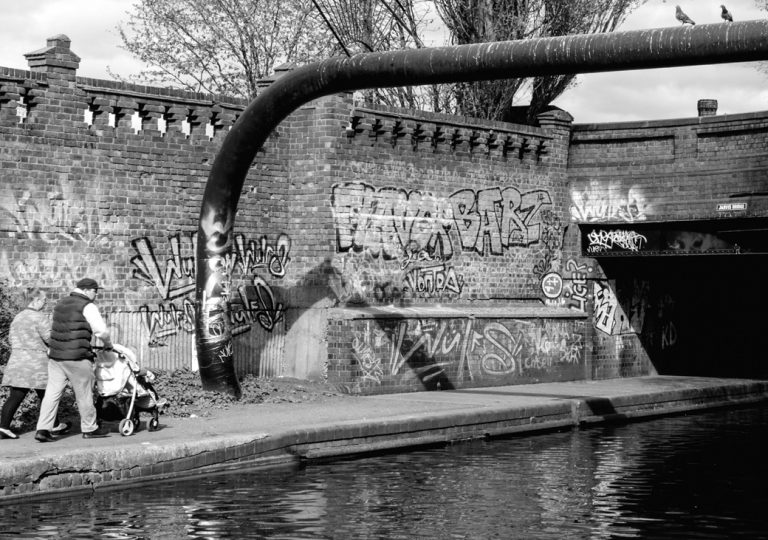

The landscape we see about us today is almost entirely manufactured, shaped by the tools of men and women, once dug into for coal and clay and canals, covered over, layers shaped and reshaped. There is little natural evidence of the past – except perhaps in Barnford Hill Park, where ‘Pudding Rock’ provides a viewpoint, a rocky outcrop formed some 300 million years ago.

It was a landscape of pollution and despoil. Industrial expansion destroyed much of the green countryside that once surrounded Oldbury, leaving spoil heaps, marl holes, quarries, pits and pollution throughout the area, and a legacy of reclaiming the land throughout the twentieth century to the present. Much of the old industrial land was cleared for new housing for the expanding population.

Percy Eamus, who worked as a Pyrometry Technician at Accles and Pollock, recalls the landscape of the Black Country at that time:

“There had been a lot more trees before the war, but a lot of them were cut down and used for fuel. In 1948, when we had that big winter, where I lived you could walk down through some fields to the canal and there were pit banks that were grown over; people were mining into there to dig out what we called ‘nutty slack’ – it would burn sufficiently. How people weren’t killed I don’t know, as they went in quite deep. There was an outlet there from the nut and bolt factory and the pipe had broken open and you used to get untreated sludge from the machining operations forming pools and puddles or rivulets. There was a structure over the top of old pit and we used to love throwing a brick over it and counting how long before you heard it go splash. That’s what finished the pits here - they were all wet pits. Next to our house was a big brick built building, and there was a machine shop. You’d be in the garden and the walls were throbbing and shaking about and there were these plates where wall together. Opposite was a very big garage and in that was a forge and a furnace where they stamped out the components, which they machined and then sent them on. It was remarkable the amount of back yard activity there was.”

Made in Oldbury

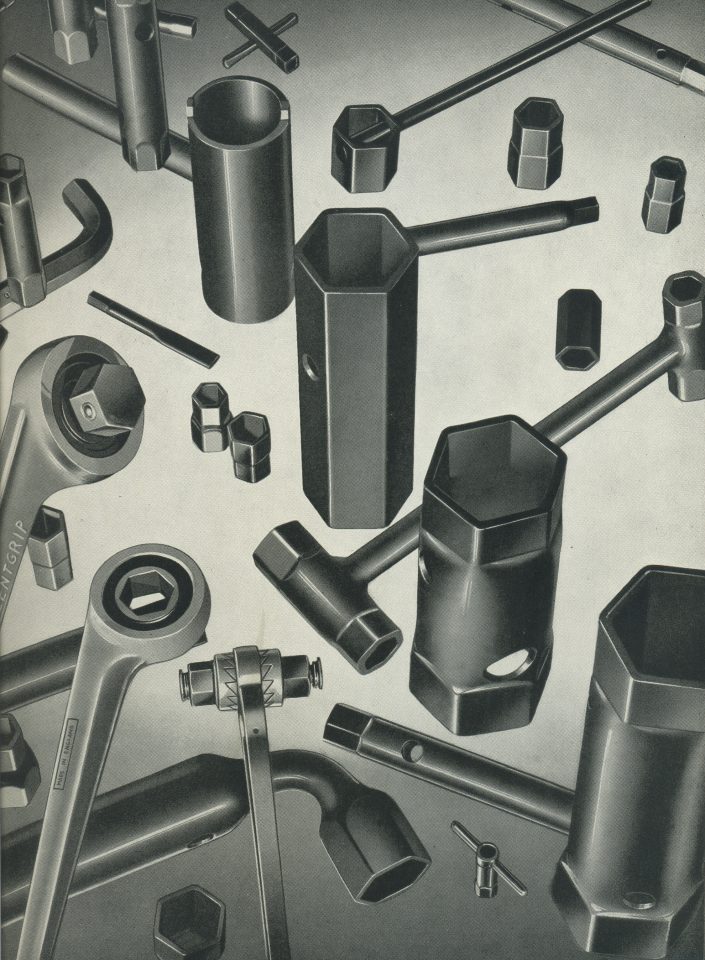

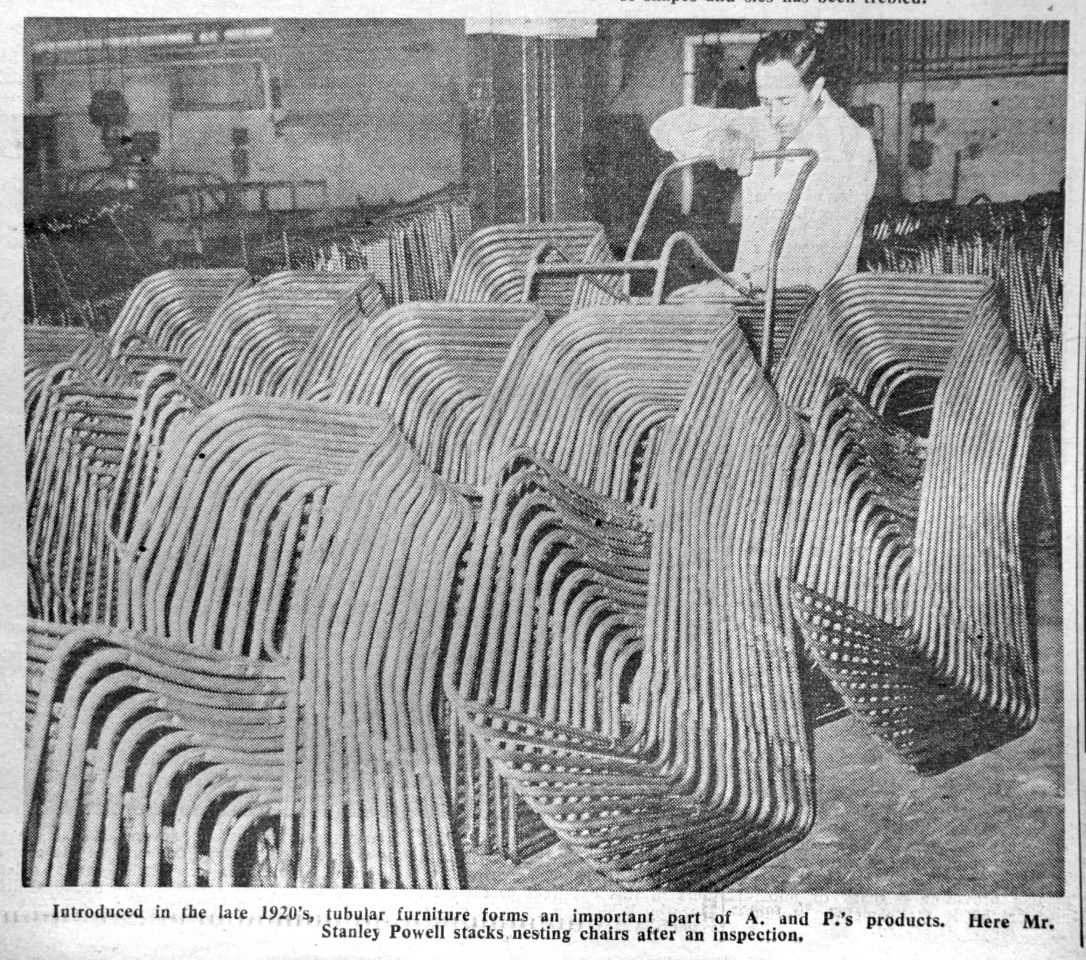

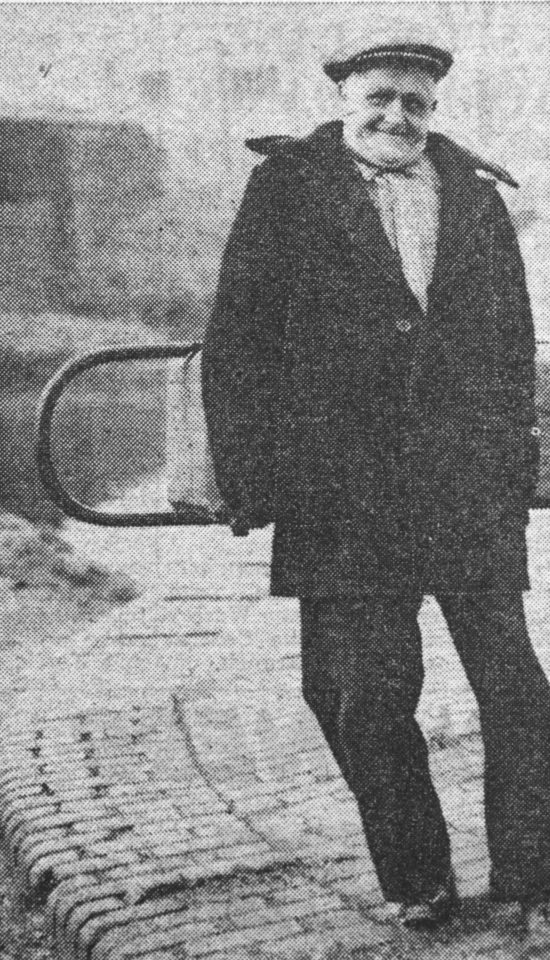

They made all kinds of stuff here. You could find steel re-rollers, metal castings, hammer and picks, machine and hand tools, welded tubes, tar and petroleum products, electric cookers and switchgears, hydraulic components. There were drop forges and furnaces, vinegar distillers, maltsters, mould makers, malleable iron founders, patternmakers, experts at metal spinning, inventors of polyester resins, boiler makers, edge tool makers, welders, chemists, polishers, galvanisers, joiners. One company, Practical Equipment Ltd of Rounds Green, formed in 1932 specifically to make steel furniture. One of their innovations was the stacking chair. This was a tubular bent steel frame painted in various colours, with a plywood seat and back rest riveted onto the frame, soon to be mass produced for schools, hospitals and businesses.

The borough of Oldbury continues to grow with new industries including the manufacture of bottles, pens, sweets and cookers. After 1945 the expansion includes a large programme of council house building on rural land.

In 1949, Oldbury Local Employment Committee stages an ‘Exhibition of local Industrial Effort’ at Langley Baths to show ‘what Oldbury makes, why Oldbury makes it, and where Oldbury products go.’ Alderman K.H. Wilson, JP, chairman of the Local Employment Committee, writes in the souvenir booklet:

‘Do you tend a machine, do you work in a filter press, do you grind an edge tool just as a means of earning your weekly wages, or do you do it with some zeal and pride? I hope this latter is the case as it is only by having this stage of production as perfect as possible that the final articles can be made without undue waste and so at prices and quantities that will satisfy the demand and help our country to recover its commercial stability.’

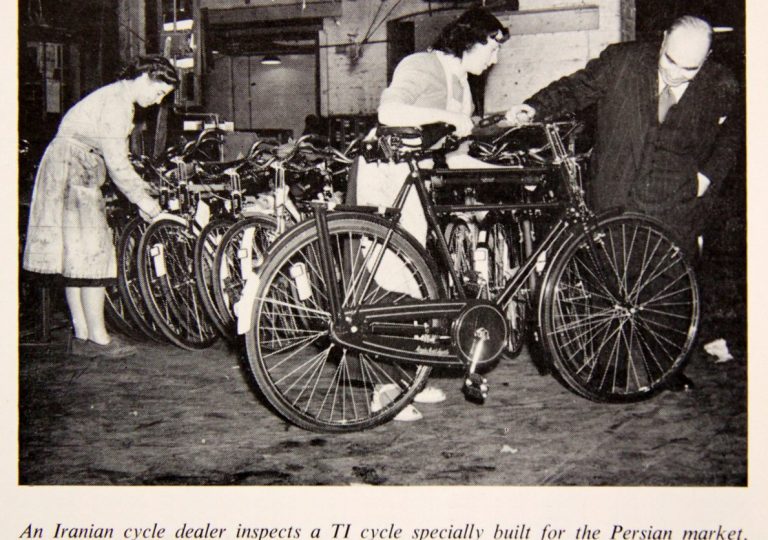

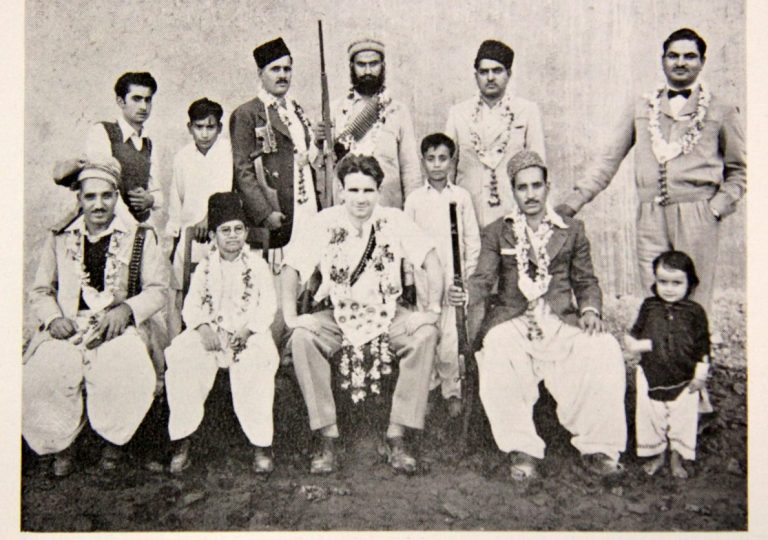

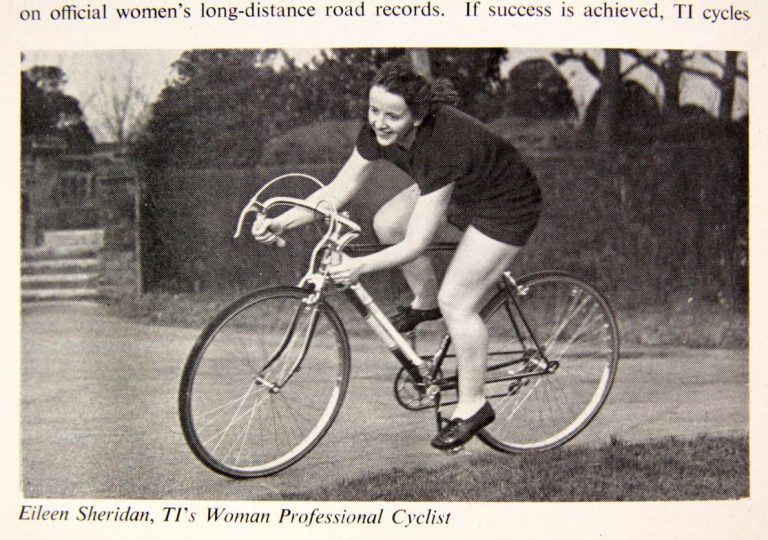

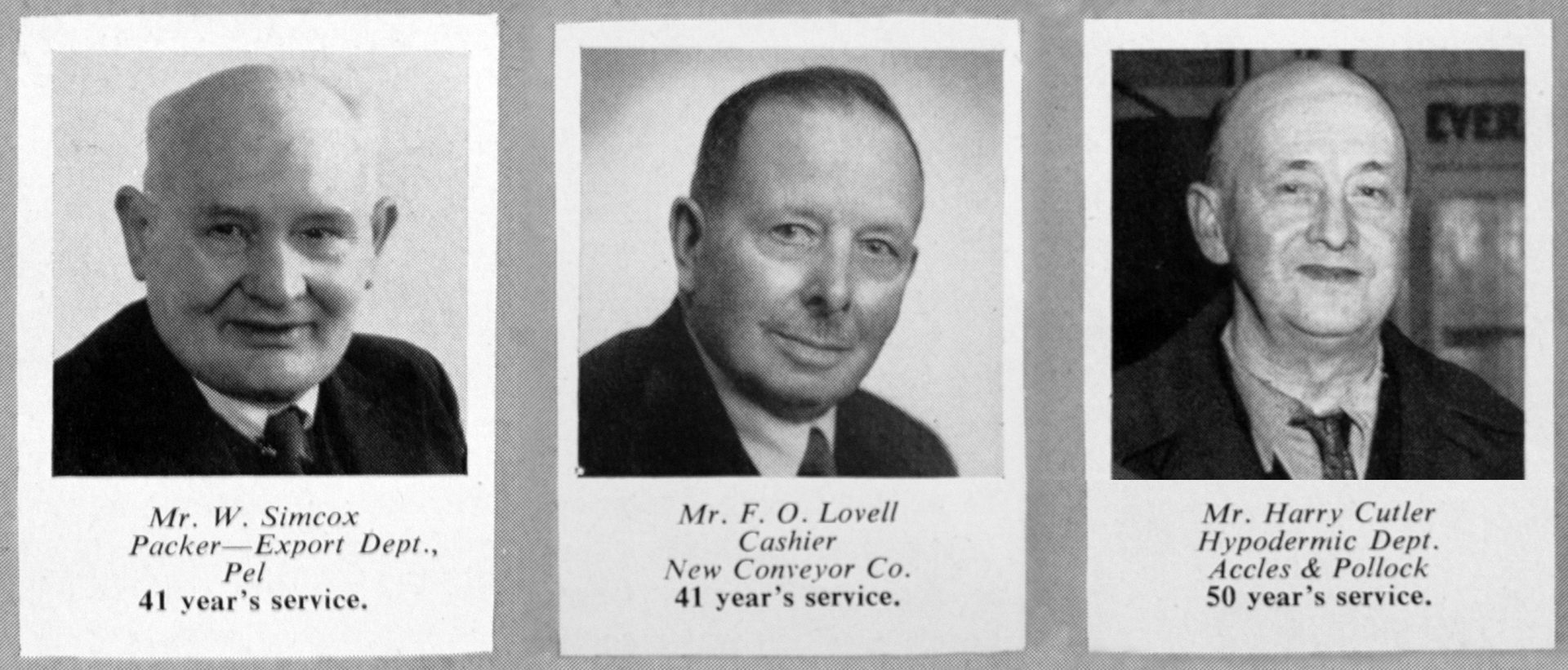

Confidence is high. Business is booming. In the 1960s the construction of the M5 motorway cuts right through the area, raised on stilts, creating a new landmark, Birchley Island. But by the 1970s and 1980s the heavy industries are in decline, subject to acquisitions, mergers and cost-cutting. Many factories close, though manufacture remains key part of the local economy. At the start of the 1970s, that most difficult decade when many firms went under, Tube Investments asked: ‘Where have all the good ideas gone?’ Proposals to the company’s Suggestions Scheme for cutting production costs and increasing productivity were thin on the ground. In the fiercely competitive modern market, they worried that reputation was simply not enough. As Chinese inspection teams arrived, TI stressed their excellent customer service and quality control. This was not a new or unusual idea. Their training booklets in the 1950s, such as ‘A Guide to the Proper Treatment of Factory Visitors’, spoke of the need to treat people well, whether they came from ‘Basra or Bloxwich’, whether it was ‘a visit of an apprentice society, a sociologist investigating the incidence of sleepy sickness among office boys, or the Sultan of Zanzibar.’ They were all potential customers. They highlighted the importance of understanding other languages and being attentive, noting ‘they will be probably hurt if they speak good English and you insist on talking to them in bad Portuguese.’ Furthermore, they emphasised,

‘Do not think it amusing to display your ignorance of overseas visitors’ institutions.’

They saw themselves as ambassadors to the world outside, able to work in an extreme of climate, in a strange tongue, surviving ‘the first onslaught of strange foods.’ With persistence, before long, Mexican and Pakistani milkmen will be cycling to work on Oldbury tubes, foreign vaccines will be flowing through Oldbury needles, prefabricated buses will be familiar sights on the streets of Cairo and Hong Kong. As the Chairman, Lord Plowden, reminds his staff in 1970:

‘We must do what many Englishmen find so difficult to do - concentrate on things that are successful and cut out the failures.’

The Working Life

At the beginning of 1949 George Higgs is pleasantly surprised to hear he has been awarded the British Empire Medal in recognition of his meritorious civil service. (Its full name was the Medal of the Order of the British Empire for Meritorious Service.) George is aged 76 and has spent 66 of those years in the steel industry. For the last 16 years he has been working in Oldbury, where he is the head roll turner and designer at London Works (Barlows). He began his apprenticeship at the age of 11 at Roway Iron Works in West Bromwich. He has worked in Smethwick, Walsall, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Wellington and in 1932 he came to Birchley Rolling Mills in Oldbury. As a youngster he walked 13 miles a day to work and back for several years – he lived in Bearwood – the journey taking one and a half hours. He had to be at work 7am sharp, come rain or shine. He earned 1 shilling a day for 56 hours a week. During the First World War he was a member of Warwickshire Volunteers and spent weekends guarding the B.S.A. works over in Birmingham.

George regretted the attitude of young people today towards their work. He thought they just don’t stick at it, not like the old ones used to do, even though youngsters now worked much better hours compared to the past, had better wages and better factories and shops. Things were far superior these days, but all people could do was moan and complain. If only there was a better appreciation of work and people could focus on working well, he thought, then the old country might again lead the world.

News in Brief, TI Bulletin, December 1948

New Low Absence Figures Record.

Total absence figures for the three months ended 30th September 1948 at 4.24% were the lowest ever recorded for this quarter, being 94% of the 1947 figures and 84% of the 1946 figures. The improvement covers sickness, accidents and all other causes.

The TI accident figure for this quarter was 0.821. This has beaten our record for the last quarter and is once again the lowest accident rate ever recorded by TI. It shows a reduction of 18% on the figures for this period last year. The rate amongst women was particularly low. The percentages of lost time under the various heading were:

Visitors to the Tube Products factory in Oldbury are impressed by the cleanliness of the bays and the brightness of the site. The management have recently implemented a new colour scheme. The works director, Mr Norton, noted that ‘Twenty years ago it was the custom to dose the walls with whitewash and hope they would not need doing again, but we wanted something brighter than the dull greys so often used, even today. Naturally, it gets dirty, but then it can be repainted and we feel it is well worth the expense, both from an efficiency point of view and from that of the workers.’

Each piece of machinery and every one of the pipes is clearly picked out in colour, while traffic lines are marked in yellow paint. Electrical apparatus, including the five-ton travelling cranes, are painted orange, water pipes are painted blue, steam pipes red and compressed air pipes are white. The furnaces are coated with aluminium paint and the machines are green. Safety guards are painted white. The new colour scheme, while offering a bright and cheerful vista, also offers great safety measures – the crane drivers are told they now have little excuse for hitting other objects when every piece of machinery is delineated with colour.

While bicycles made with tubes from Oldbury are traveling far around the world, they are equally popular at home. At Oldbury Juvenile Court a 14-year old boy is charged with stealing a cycle worth £20. The boy appears with two others, who are all accused of stealing valuable cycles, one of them worth £22, stripping them of their wheels, lights and other parts, before throwing the frames into the canal. Two of the boys admitted the thefts and were bound over for two years and ordered to pay 11 shillings and 3 pence costs. The third boy was sent to a remand home for a fortnight. When his mother stated she had not informed her husband of the boy’s appearance in court, the Clerk to the Justices Mr Larkham made the following comment: ‘One hundred and fifty years ago this woman would have been hung.’ Parental responsibility was not quite what it used to be.

Meanwhile Frank Davis, aged 41, of Newbury Lane appears before Oldbury magistrates court, along with his wife Edith. They were accused of stealing bricks from Pratt’s Brickyard in Brades Village. A police officer had visited the defendant’s home and found there a new garden path made from a number of bricks. Davis had admitted to the policeman that he had taken them from a tip near to the brickyard in question. He claimed that he had done no harm in taking them and that he did not realise that it was an act of theft. His wife said that there had been lots of other people taking bricks and she did not see why they were being picked on. The owner of the brickyard, Joseph Arthur Pratt, claimed the bricks were worth at least £2 and had come originally from an old air raid shelter. The couple were found guilty and Davis was fined £4 and his wife £1.

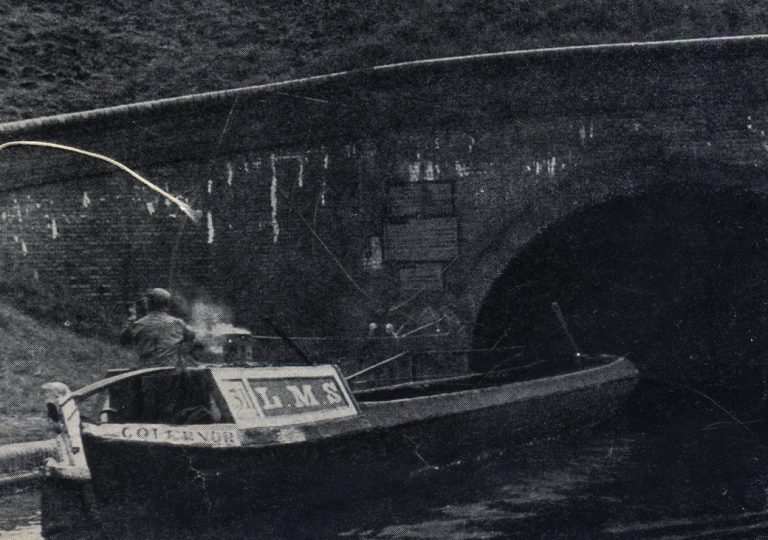

They said it was the loneliest job in Oldbury – a toll house situated on a tiny island on the New Main Line canal. Once one of the busiest waterways in the Black Country, the canal was originally dug in the 1820s. Since the end of the Second World War there has been a marked decline in trade. Two toll collectors work here each day. Joe Whitehouse starts at 6 am and finishes at 1.30pm, while A.J. Calloway arrives at 11.30am and remains on duty till 7 pm. Joe recalls seeing the old ‘Josher’ boatmen wearing their white silk shirts and velvet suits, their wives in voluminous skirts which gloriously swept the ground. (‘Josher’ was a particular style of curved fore-end on a boat built for Joshua Fellows of Fellows, Morton and Clayton, one of the best-known canal companies, originally started by James Fellows of West Bromwich in 1937.)

They both agree that the skills and character of those old-timers are sorely missing now. Today, a day’s traffic consists of some 30 barges, mostly moving between Wolverhampton and Birmingham, transporting coal, the by-products of tar distillation or rubbish from local factories.

When a barge passes the toll, the collector must measure the boat’s draught – this is used to determine the weight of the cargo on board by calculating the total displacement of water and then using Archimedes principle. He collects a list of the cargo from the boatman and enters the details into his log. This only takes a matter of minutes, and then they wait for the appearance of the next boat. When Joe used to work nights, he could set his watch by the Gloucester barges; they always arrived at 4am in the morning and it was a terrible job on a winter’s night, clambering over the boats piled high with boxes of matches, the weigh bills in one hand, the lantern in the other. But there’s plenty of time for reading these days, not like the old days when it was so busy you didn’t have time to grab your lunch. To entertain themselves they take cuttings from the newspapers which relate to canal life and paste them on the wall. It’s become quite a display. They are waiting for the day a long promised electric light will be installed in the toll house to replace the storm lanterns they currently use after dusk.

Food was once a big cargo on these waterways - sugar, wheat and beer used to pass through Oldbury and the toll keepers kept an empty jug handy to sample a pint or two. A.J. used to work at Winson Green before the war, near to the walls of the prison, which he found an even more forlorn place. There he couldn’t swing out a plank to get ashore, as he does at Oldbury, but instead had to throw down baulks of timber to cross over. He remembers one night he heard a voice calling out from the path and he found a man standing there covered in blood. The man had attempted suicide by cutting his throat and intended to throw himself into the water. What a palaver that was! Folk do have some strange ideas.

Alf Safe was brought up with his brothers and sister on the boats in the 1930s. His parents worked for the Grand Union Canal, carrying timber and coal locally. They also worked for Thomas Clayton, carrying oil from Manchester and Ellesmere Port to the BP depot in Langley – a round trip of six days, passing some 60 locks en route. These required boats made of oak, 71 feet long, with several compartments with covered tops into which the oil was pumped. Living quarters were at both ends of the barge, a little cramped for a large family. His sister, several years older, was responsible for his education until he was 10, when he finally attended school. He recalled being as fit as a fiddle, which he put down to the hard work and the open-air life. Food was plentiful – with pheasants, ducks and rabbits traded with gamekeepers along the way, fresh vegetables and eggs bought from cottages. As the work of boatmen was considered a ‘reserved occupation’, Alf was not called up to the army. He spent the war years working for Clayton, delivering the oil, and ferrying materials for the Chance and Hunt chemical works. As the haulage work on the canals began to disappear in the early 1950s, he went to work as a lorry driver for British Rail, and then in 1959 went to work as a driver for Albright & Wilson.

By 1957 Charlie Davies has been lockman at Titford Top Lock for eight years. He feels bargees are a dying breed.

‘People on the boats are not like they used to be; not so sociable, they lack a smile; their existence has slowly deteriorated, their candle is almost out.’

The growth of motor transport is to blame, sapping the income of the bargees. Money is getting hard to come by - the summer months in particular. In winter a two-man barge team might reasonably earn up to £18, not a fortune these days. The canals are being filled in, especially basins, the land soon becoming sites for house building. The Weekly News reporter is non too impressed by their nomadic ways or ‘their gluttony for bright bohemian clothing, their brass horse strappings, rosettes and their decorative cutlery and plates.’ He struggles for words to describe the canals of Oldbury and comes up with

‘stinking, smelly, filthy, revolting, sickly...’

One of the photographs is captioned: ‘How do the kids spend their leisure time? “Mucking about with old rusty tins and chunks of wood” says the bargees of tomorrow.’ As he watches the barge children play around the boat yards at Tat Bank, amidst the rusty scrap and rotten wood, noting their lack of statutory schooling, he decides ‘impure’ is the more tender expression. And so he writes:

‘The impure canals are alive with vermin; canals locally are a lavatory, a garbage refuse, a floating sewage.’

It’s the beginning of 1949 and the world is still spinning

The intricately stitched together tapestry of the Empire is unraveling. While we peer into the pages of history, they look forward to new age, the Atomic Age. The Nazis and the Japanese have been beaten, though an Iron Curtain has now fallen over half of Europe, with the Red Army in Warsaw, Berlin and Prague. Winston Churchill is drafting his landmark speech in support of the idea of a European Union, which he delivers in May at the opening of the Congress of Europe at The Hague. Over four days, 17,000 people visit the ‘Made in Oldbury’ exhibition at Langley Baths. A brighter future is surely about to unfold, despite the inconveniences of power cuts and fuel shortages. Order books are filling again. We are all dreamers, taking a leap into the unknown. The world’s first passenger jet, the de Havilland Comet is about to take to the air. Able to fly higher and faster, this secret test flight will revolutionise air travel. It is entirely British built, with steel tubing and rivets from Accles & Pollock, carbon steel and alloy steel from Hughes Johnson Stampings, and Metal Sections providing tungum tube and rolled stringer sections.

No-one here is aware the US Army Air Force had put forward a plan to the Pentagon the previous September to destroy 66 Soviet cities and were demanding production of 204 atomic bombs to do so. As it was, production of 39 were approved to eliminate 15 first priority targets. Among them, it was estimated 6 each would be required for Moscow, Leningrad and Kiev, 5 for Lviv, 4 for Chelyabinsk, 3 for Tbilisi, 2 each for Baku and Grozny. While the majority of his cabinet and nuclear scientists support the idea of international collaboration to control nuclear power and the abandonment of ‘the policy of secrecy’, the President sides with the military establishment and as the Soviets successfully test their first nuclear device in August, the arms race begins.

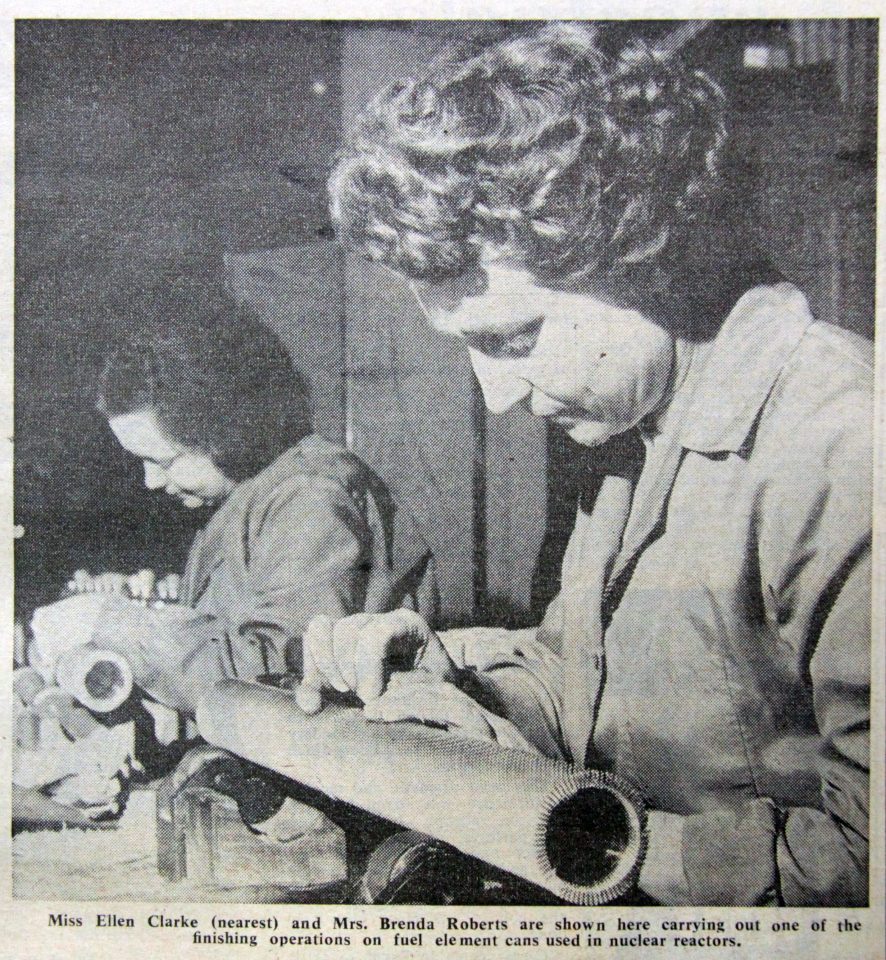

While the nuclear power industry will be lucrative new market for Accles & Pollock, Walter Hackett is worrying that new developments in plastics and glass technology will supplant the need for metal tubes, his old colleague Captain Jack Seddon is featured in a publication celebrating the Jubilee anniversary of the firm. He recalls:

‘There was I, a young lieutenant, who’d just spent a lot of time and money on building the world’s first metal aircraft – and it hadn’t flown. And there was this Very Important Personage declaiming ‘Don’t be a fool man. Steel tubes will never fly!’’

Accles & Pollock began work on the world’s first metal- framed aircraft in 1906, a twin engined tandem biplane with a span of 50 feet. In November, 1910, it was tested at Dunstall Park Wolverhampton, home of the Midland Aero Club. Called the Mayfly, designed by Seddon, it was made with over 2,000 foot of light gauge  tubular steel hoops. He was inspired by fellow officers playing with paper gliders and had spent 3 years in Ceylon making models with wire hoops and elastic. The metal plane seemed to onlookers to be too heavy to actually fly.

tubular steel hoops. He was inspired by fellow officers playing with paper gliders and had spent 3 years in Ceylon making models with wire hoops and elastic. The metal plane seemed to onlookers to be too heavy to actually fly.

On its first high-speed ground run, it suffered irreparable damage; the engines failed to work simultaneously, one propeller disintegrated, an engine chain broke, a wheel collapsed. Though the real problem, according to Seddon, was that it was far too light to be controllable in the air. Repairs and modifications were hampered by his subsequent unavailability due to his service commitments and there were no further tests. It never got off the ground. The aircraft was soon dismantled by souvenir hunters.

Nevertheless, by the 1950s Accles & Pollock are supplying metal tubing for retractable undercarriages, engine mountings, exhaust manifolds, airframes and jet engines, for every type of aircraft built in Britain, as well as in rocketry and guided missiles. At that time, Bob Beard was a Senior Engineer at the works and a proud member of the British Interplanetary Society. On the factory floor they joked about his hobby, telling him loudly and often,

‘Bob, we’ve never going to go to the moon.’ But the future, at least one kind of possible future, was being made in Oldbury.

Roger Chadburne has an accent as broad and deep as the cut itself. Newly married, he moved into the new blocks of flats built at Brades, which offered a grand view of the landscape. He enjoyed the flat and particularly recalls the three bar electric fire set high on the wall of the living room. His work experiences were mixed.

“We lived on the ninth floor. They were two bedroom flats. We looked down over at the main gate to the Brades factory and the Brades clock - they made shovels and gardening tools. I used to work at Brookes, cleaning up, putting all the suds in the machine and cleaning them out. My first job in Oldbury was at Accles, doing sandblasting. The machine blew up in my face. I had poisoning and I was in hospital, the old one at West Brom. As they took me away they said, ‘If you don’t come back, you’ve lost your job.’ But then in the hospital they burned all my working clothes. All the lot. My coat was hanging on the wall, they took it and burned that, and I never got back my flask or my lunch box. So when I got out I went back to work in my wedding suit, still got the flower in. I got through the door and they said, ‘You’ve got the sack’ but they took me back on in the end. I’ve worked in six different foundries, two brickyards, three building firms. I loved the building work. I left this one job and went into making kettles and saucepans; it just before Christmas, I was there in time for the Christmas party. Went back just after the Christmas break and the boss said, ‘Last in, first out.’ He’d just sold the business. In the 1980s, with all the unemployment, I did four different courses to get retrained but nothing came out of them. Once they sent a letter down to the Job Centre I had to go to, saying I was now an electrician. I’d only done a month course for that. I didn’t know much. You’re supposed to do three years to be an electrician.”

The Leisure Society

The factory offers a strong sense of community and working class solidarity, as well as meaning and purpose. But to nourish the spirit and soul the factory owners, many of them originally Quakers, also provide a social network. In July 1872, Albright and Wilson organised their first annual works trip for the men and their wives, providing free transport - 400 went by special train to Alton Towers. In 1880, they set up an Accident and Insurance Society, managed by a committee of workmen consisting of 5 foremen and 7 workmen. Other firms soon followed their lead.

There are all kinds of clubs and societies in Oldbury, mostly supported by subscriptions - for angling, bowls, billiards, snooker, darts (with Ladies and Men’s sections), table tennis, skittles, archery. They establish sports facilities with football, cricket and hockey teams, athletics meetings and competitions - as well as indoor rifles and ‘physical culture’ classes. They run children’s parties, youth clubs, summer camps and adventure centres in Wales. There are photographic and operatic societies, horticultural and drama clubs, public dances with live bands, arts and craft shows. Accles and Pollock even have a works library, with a branch at each of their sites - the fee for use is 1 shilling a year.

Albright and Wilson characterised itself as:

‘Not just a factory... more a way of life. The Oldbury factory is rich in characters, stories of personal endeavour, family service, Quaker virtues and above all, humour and humanity.’

Pat Sealey, who worked there, recalls: ‘It was the biggest factory at Oldbury and it was very sociable. The club in Station Road, which is still there (now called the Solvay Suite) had an active drama group. We’d rehearse for weeks for three nights performance. As well as the dramatic society, we had the sports fields where we played tennis, off Tat Bank Road. We’d play against the London office and other factories at weekends. They used to have inter-factory competitions for everything, not just the sports but the first aid teams and the fire drill teams as well.’

In April 1959, she performed with the A & W Dramatic Section in ‘Dead on Nine’ by Jack Popplewell. The plot was summarised as: ‘Robert and Esmeralda Leigh had intended to kill each other, yet Esmeralda ends up shooting Robert’s lover Marion, while Robert pushes Esmeralda’s boyfriend off a cliff. Their alibis prove to be unshakeable. This being so, Inspector Farrow tries to convict each of the murderers for the other’s deed. A cruel game commences...’ As Esmeralda, the play called on Pat to be slapped convincingly every night by her stage husband.

Harry Hammond organised events at Birchley Pavilion, owned by Accles & Pollock. In 1954, he offered this advice on forgetting the cares of the workaday world:

‘Some departments favour artistes for the benefit of the non-dancers during the first half of the evening. Keep the shows short and snappy. Don’t let them run past 9.30. The basic idea of a social is a get together, and the meetings in the bar are apt to become somewhat noisy. A late-comer feeling thirsty wouldn’t want to listen to Gigli anyway!’

In 1964, the TI Social Club has over 1000 active members. It ranks itself as one of the finest social and recreational centres in the country. It is tastefully decorated and has a pleasant atmosphere. There are 26 teams of men and women in two 9-pin skittle leagues, which run every night between September and March. It has 8 full-size tables for billiards and snooker. It has a table-tennis room, a badminton court and an indoor range for .22 rifle and archery. The Photographic Society have a darkroom and lecture room. The Operatic Society have 60 members who also rehearse here, staging their annual Gilbert and Sullivan opera in October. The Club has recently installed a cocktail bar. Dances, old-time and modern sequence, are held every Monday night. The tickets for the Annual Ball, with Victor Sylvester and his Orchestra, quickly sell out. The annual club subscription is: ‘Employed within 3 miles of the club, male 5s, female 2s 6d, juniors (15-18) 1s; Affiliated, employed beyond three miles of the club, male 2s, female 1s.’

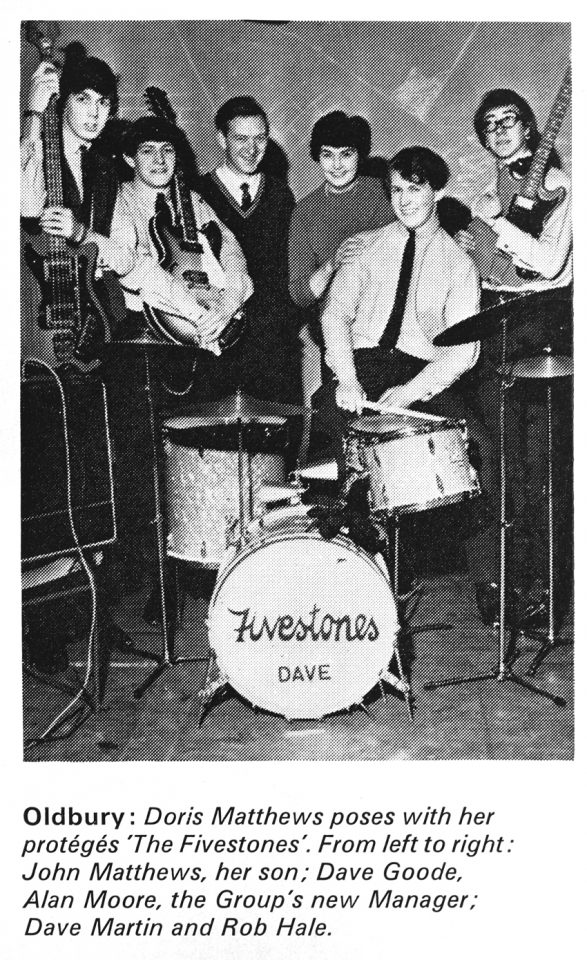

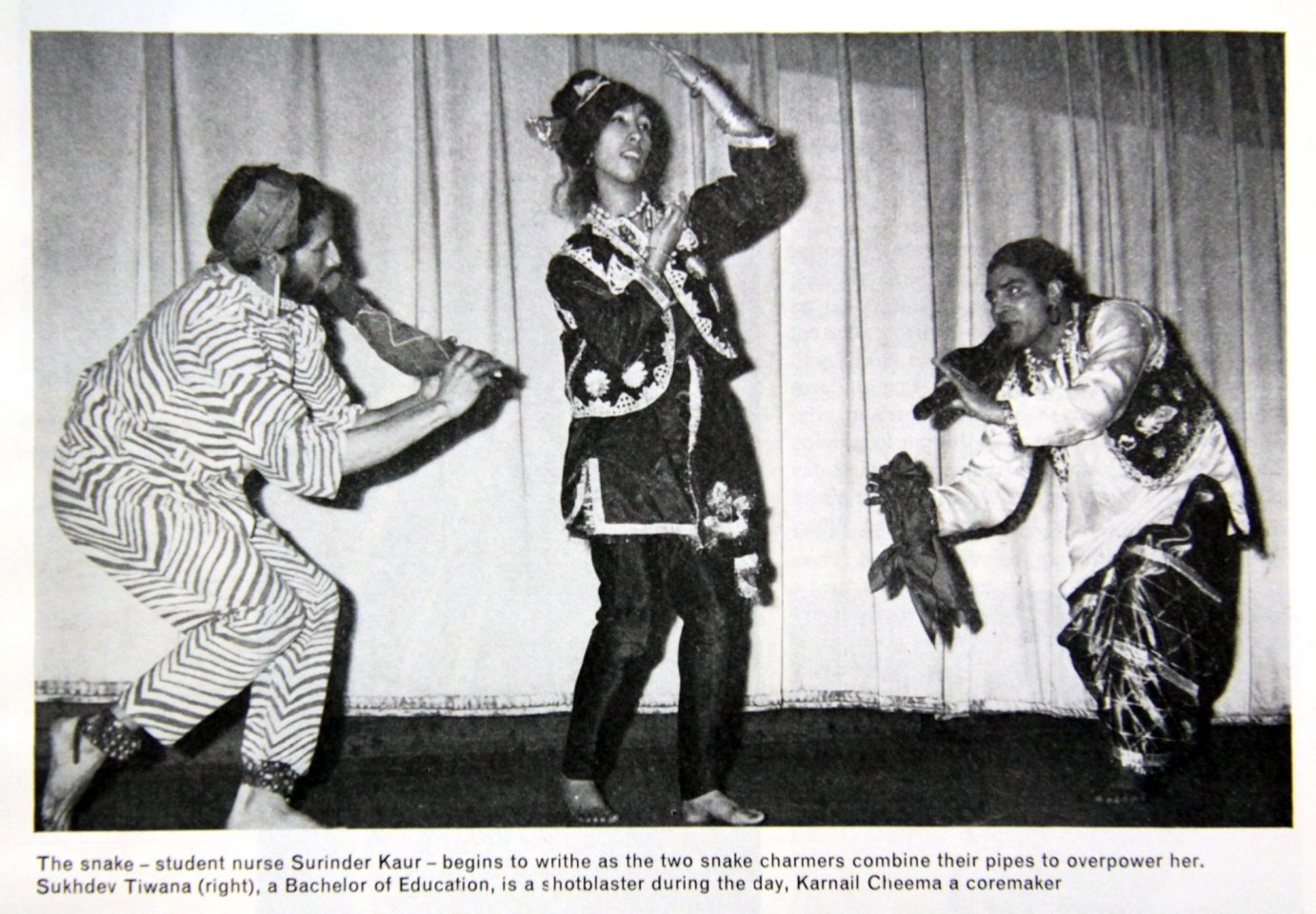

And the beat goes on. In 1970, a group from the foundry in Oldbury offers to provide the entertainment for the Simplex annual Christmas party at Trentham Gardens. Expecting the usual style of cabaret, the workers are treated instead to ‘a touch of Oriental splendour.’ The Sathies - or Comrades - are 16 dancers and musicians all originally from the Punjab. There is one woman amongst them, student nurse Surinder Kaur. They performed traditional stories from their homeland with mime and dance, tales of snake charmers and farmers. They played the Tapla and Dhol, Hawaiian guitar, the one-stringed star shaped Tumbli, as well as the electric organ. Founded by shotblaster Sukdev Tiwana, a Batchelor of Education, and Resham and Jernail Dosangh, who both work by day as dressers trimming the castings, they rehearse one night a week and have thus far given over 130 performances, mostly for charitable causes.

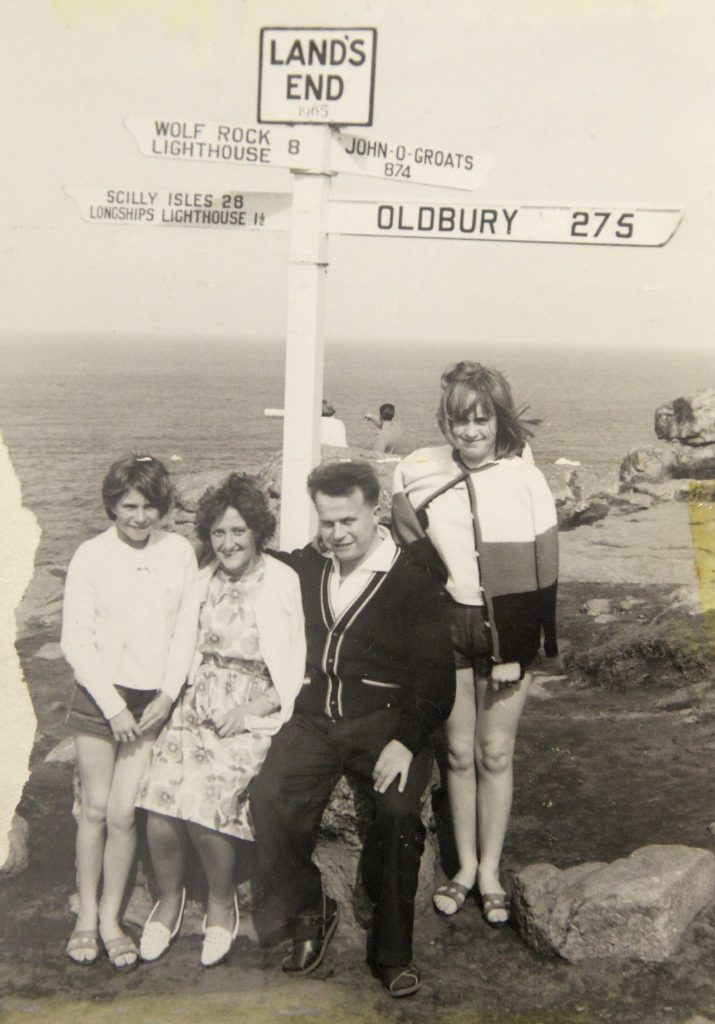

Land's End, 1960s. Photograph courtesy of Janette Callaghan.

Interactive Journey Credits:

Words & Design: Brendan Jackson.

Contemporary film footage: Geoff Broadway.

Industrial sounds: Sounds of a Different Realm Sound Effects: (the brilliant work of sound designers Alan Splet and Ann Kroeber).

Archive Film Footage edited with Beverley Harvey from: ‘Start of A Career’, 1964. Training film from Accles and Pollocks, courtesy of Sandwell Community History and Archives Service. The original soundtrack has been lost; ‘The Safety Factor’, Albright and Wilson, 1986.

Town Sparrows, silent monochrome film made by Frank Wakeman in the 1940s, courtesy of Oldbury Local History Society. The original can be viewed here: http://www.historyofoldbury.co.uk/2gallery2.htm

Images sourced from the collections of Sandwell Community History and Archives Services (CHAS) and Langley and Oldbury Local History Society, except where individually credited.