Roy Taylor was born in Dudley. At the age of 39, he became Malthouse’s Managing Director designate.

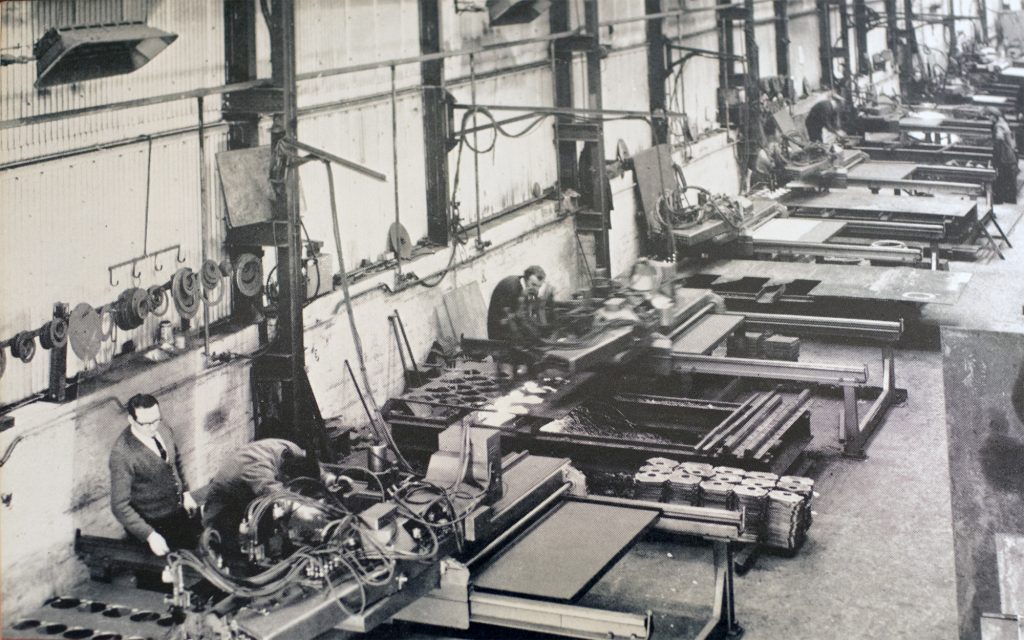

“When I first started here in 1983 we had a turnover of £1.5 million. It’s now in the area of £10 million, with another £2 million from our Wednesbury site. We’ve acquired other companies and grown. We were employing 49 people then, now it’s around 80-90 depending on demand. Our business is flame cutting. The flame cutting machines we use are multi-headed. This means they can be operated with either one torch for big one off profiles or up to six torches for batch multi-cut profiles. We get an order, type in the details to the computer and we draw in the profiles and work out how to utilise the steel plate in the best possible way. So one plate might have the profiles from 20 different customers – we call this ‘nesting’, to organise it to the best efficiency we can. The operator then puts the programme on the machine and it will run it and cut it. The first computer we had was a BBC, which was difficult to programme. Computers allow us to do things much more efficiently. The problem in the old days was you’d take a drawing from in the office, where it was nice and warm, to out there where it was damp – and you would get some shrinkage.

We cut from as thin as 8mm thick up to 500mm thick. The steel mainly comes from a company in Gateshead, called Spartan, up to 160mm. Anything heavier than that has to come from Germany. There’s 42 different industries that we provide the work for – obviously there’s a lot done for press tools, pressing and forming steel, and for plastic moulding tools, automotive and aerospace tooling, for medical fields, agricultural machines. We do parts for bridges. We’ve also been doing work for alternative energy – flame cuts for wind farms, and now for tidal power stations. We’re currently making specific parts for a new machine that’s something similar to the Hadron Collider in Geneva, large lumps of steel precisely formed, which are being built into this 300 metre diameter structure. We’re not high volume yellow goods. Our business is small volume, bespoke, one offs, ten offs and we’ll probably never see that particular shape again.

On a trade delegation in 1999 to Japan we saw a way to reclaim the little bits of steel leftover from cutting the shapes, the bits of metal that fall through to the bed, which are bombarded with all the other stuff, the iron oxide from the cutting, which builds up and builds up so when you come to throw it away you’re throwing that away plus the bits of metal. These bits of metal are more and more valuable, so we designed a machine, a ‘scraper conveyor’ and patented it. This scrapes all these items away from under the profiling machines and separates them. The iron oxide dross goes into one bin and the steel into another. The iron oxide you have to pay to take it away, but for the steel bits you get up to £250 a ton - it’s been as much as £328 a ton. That drops to the bottom line as profit. It also enables us to have one man on two machines, as he’s not having to spend time dragging out this dross, creating dust and noise. Having it done automatically at the end of a period when a machine needs to be cleaned is a more effective way of doing things.

We have an employee suggestion scheme here. The winner gets £50; after six months the best six are put together and the winner gets £500. One of the winners was an idea for rainwater harvesting. We have these Lumsden grinders, which use a lot of water as a coolant, as they grind the steel from the black to the polished. We have a 120 inch machine, a 100 inch, and 84 inch and these 60 inches machines. So we take all the rainwater off the roof into the system as a cooling water; we don’t take anything from the mains. The employee idea was to reuse these intermediate bulk containers - we’ve got 32 at the back. It cost us £168 to get a bit of tubing from B&Q to connect them all together to make a reservoir and pump it into the factory. It’s a bit Heath Robinson but it works. The biggest expense is the UV light which bombards the water as it goes through the pipe to kill the bacteria. I’ve given lectures on that to Birmingham City University. They were enthralled with it.

I first worked at British Steel, in Brockmore, Brierley Hill, where they made transformers and electrical motors. I did my apprenticeship there. I was in my final year there when I met a young lady called Sheila, who became my wife. She was brought up in Brades Village and worked at Malthouse Engineering. She had started there at the age of 17 as an office junior and two years later she became secretary to the Managing Director, Bert Hands. So I first became friendly with Bert as a result of that. When Bert was going to retire he suggested I apply for the job.

Sheila’s mother’s maiden name was Price and when we found out there were three malthouses in Oldbury and Langley and each of them was looked after by her forebears, that was quite an amazing coincidence. My father couldn’t understand why I wanted to go into engineering when I was 16 - he was a fruit and vegetable man. When we did our family history I found out my own forebears were actually anvil makers who also travelled all the way to Cradley Heath to make chains as well.

As a young lad, I knew this site, where Malthouse is today, as we had some family friends who moved onto the BIrmingham New Road, there were some really nice houses being built there in the late 40s. On one or two occasions in the summer we would visit them on a Sunday evening. Around here then, it was just rubbish dumps. The bridge, which is a footbridge now, used to carry a railway line bringing rubbish from the Oakham area, the stuff out the puddling furnaces up there, the old spent rag from Rowley Rag, and they would just dump it in piles all the way over here. On one Sunday evening, when I was about 4 or 5 years old, I can distinctly remember young men, about 12, 13, 14 year olds, on any bikes they could find having races round these piles of rubbish and there would be people betting on them as to who would win. 35 years later I ended up as Managing Director here.”