Pat Sealey left school in 1953, went to college for a year, then she went to work at BIP in Tat Bank Road. In 1955, she took up an opportunity to work at Albright & Wilson.

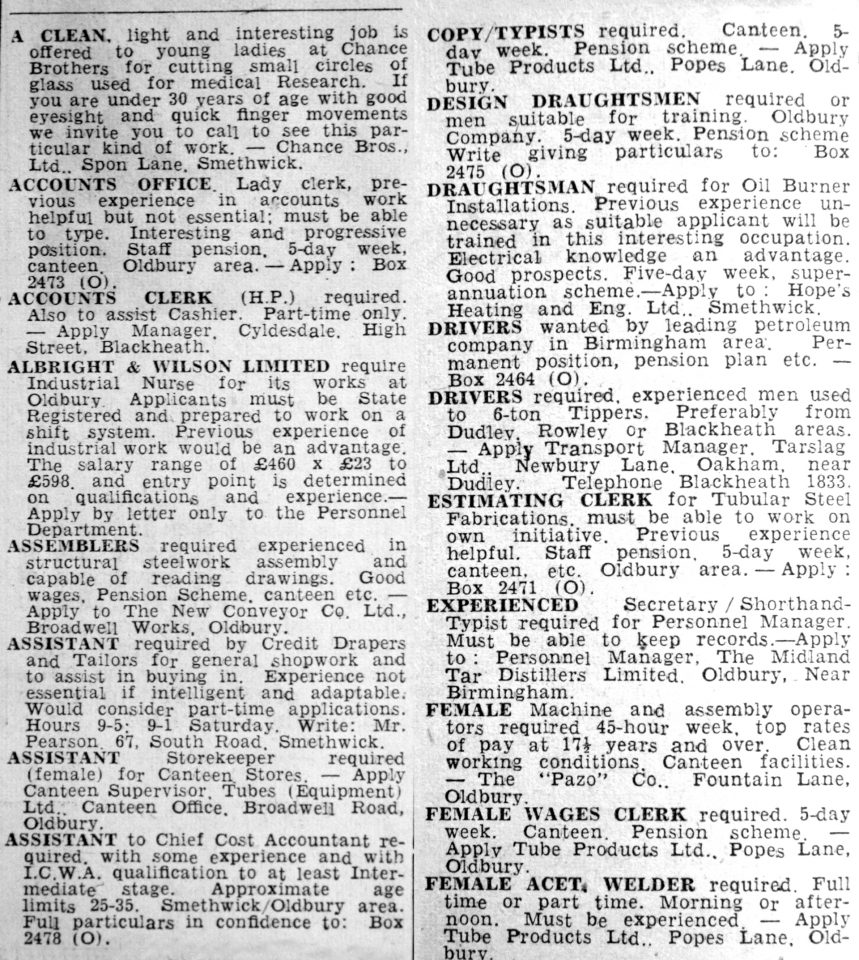

“I did a full-time secretarial course when I left school. I didn’t want to be a nurse or a teacher or go to university. I wanted to be a secretary. I got a job at BIP, and worked as a shorthand typist in the purchasing department, which was very good for me, as it increased my typing speed. Then I saw this job advertised for the Chief Medical Officer, Dr. John Hughes, who covered all the factories of Albright & Wilson, but he was based at Oldbury. So I applied and went to work for him as his secretary. Originally we worked in the clinic, that was at the Langley end of the Oxford, then as things grew they formed a central personnel office and we moved over the road into an office block. He was a very nice man to work for.

It was a big factory at Oldbury. It was the biggest, and it was very sociable. I don’t know whether that was because the Albrights were Quakers originally and had this strong ethos of looking after their staff. It had a 24-hour nursing service. Medical and dental care were given a high priority and no-one was allowed to work on the factory floor if they had a cavity because of the risk of an industrial disease called Phossy Jaw. So there were excellent medical and dental facilities at all factories. And they had a big research department. Because of the nature of the product they had a thing called the Toxicality Committee, and my boss was on it. They did do animal testing, not here but at Huntington. It was very contentious, even then. The products were used in food additives, margarine wrappers, toothpaste, all sorts of things, so there was always a big argument about that. They developed a flameproof product called PROBAN®, for night dresses, night clothes.

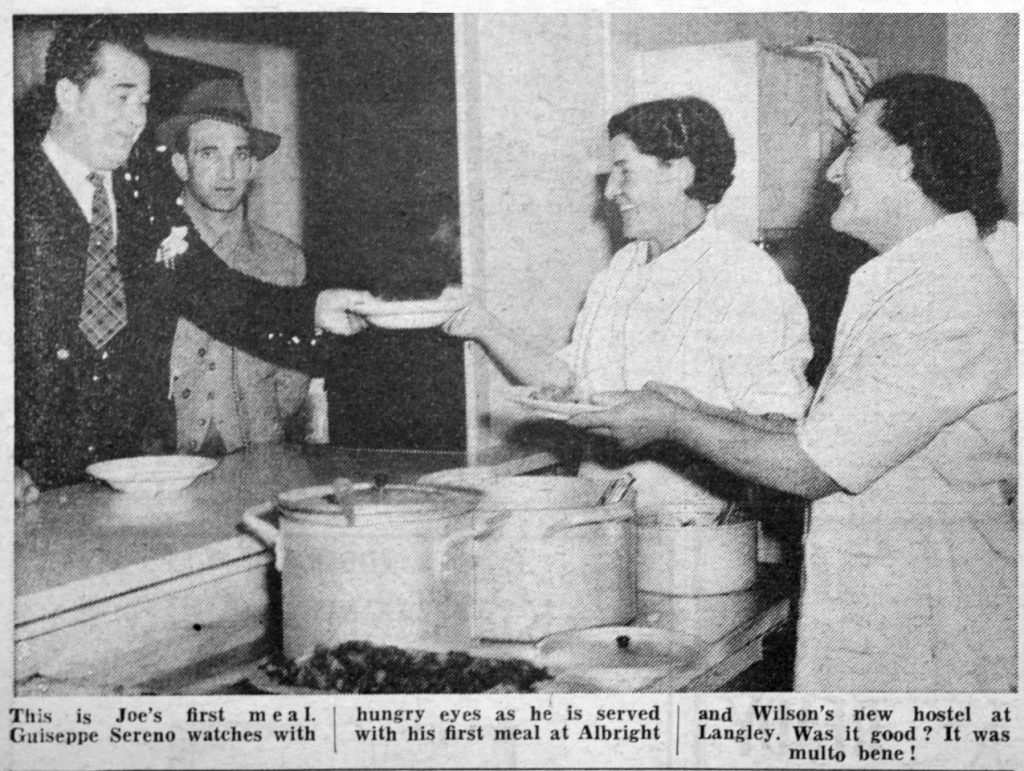

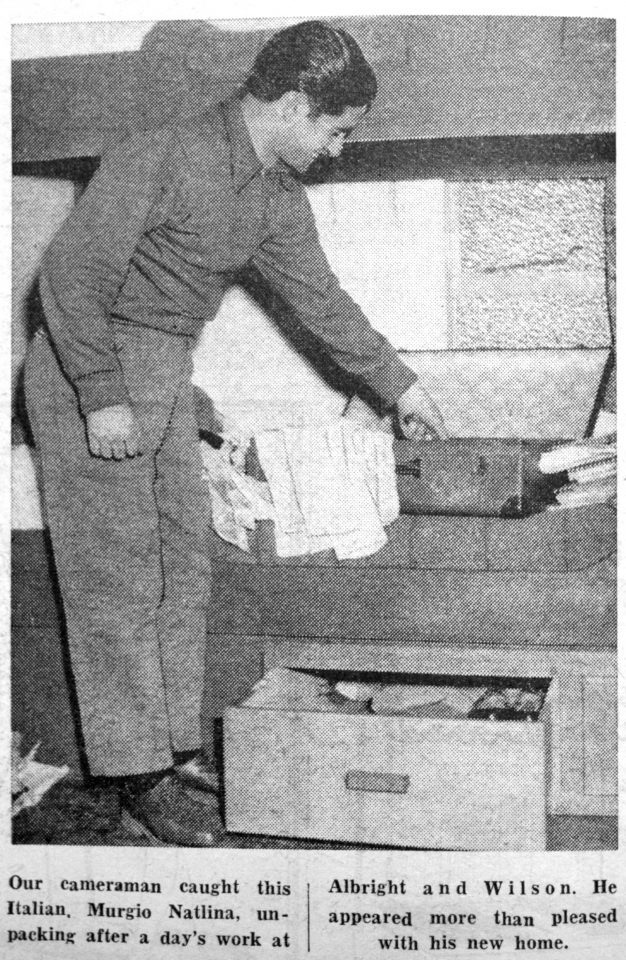

It was really interesting because of the nature of the processes there and the danger, there was huge danger. I was in the clinic and you saw a lot going on, I was quite young. The first time I saw someone come in with a blow back at the furnace. They were given safety equipment but they didn’t bother; they didn’t lace the boots up so all the slurry would go inside the boots. They used to thrown them into a bath, full of water, with potassium permanganate, because it would turn the phosphorus black and then they’d pick off with tweezers. I couldn’t believe it. It was horrific. Of course, the poor soul was screaming their head off, that was before they were dashed off to the Birmingham accident hospital or the eye hospital. There had a lot of problems with eyes, with a product called Malathion, which was very dangerous for the eyes. I saw a lot of that. It was informative. Sister Barfield frightened me to death. She frightened everybody to death. She was formidable, but I’m sure she ran a good ship. It was a time when they had problems getting men to work on the floor, understandably, so they went out to Italy and the West Indies to recruit. They tended to have quite a few accidents at first until they got used to things. Of course, I was a young woman and the Italians were very charming. I had a good time. There was a hostel in Langley where a lot of them lived. It was quite a mixed community at the time I was working there.

They placed a lot of importance on providing facilities for sports and looking after their staff. When I went to Albrights I was put immediately into a non-contributory pension scheme, which was extraordinary. It was unheard of for anybody, but particularly for women. When I went to work for GKN later, I had to wait three years to join their pension scheme, whereas men went in after one year.

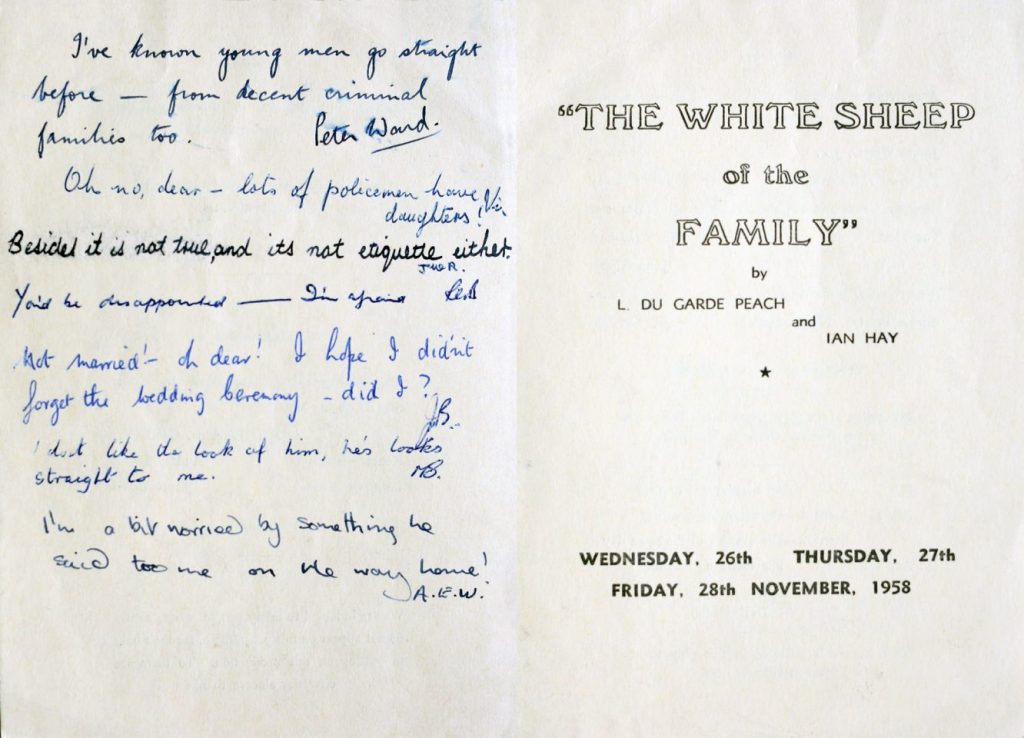

The social side was interesting. I was avid for hockey and tennis. I was involved with the tennis club at Albrights. The sports club in Station Road, which is still there today, had an active drama group. We’d rehearse for weeks for three nights performance. As well as the dramatic society, we had the sports fields where we played tennis, off Tat Bank Road. We’d play against the London office and others, and go off hiking at weekends. They used to have inter-factory competitions for everything, not just the sports but the first aid teams, the fire drill teams, as well.

Eventually my boss decided he’d be better based in London, and I went and tried it, but I thought it’s not for me. So I then went to work for the Head Organic Chemistry, a Dr Coates, but it was very scientific. The main thing I did while I was there was organise the tennis section with the head of one of his departments, because he was tennis mad as well. I remember what finished it for me there. I was typing this report and one of the chemicals took two and a half lines to type and I went into the laboratory and asked if I could see this chemical. It was white like water. I said, ‘Is that it?’ I thought it’s not me, I’m more about people. So I decided to look around. Many people were at these companies all their lives, people have long service medals, watches, clocks when they left. I think it’s a bit sad to get a clock when you retire – you don’t want to be clock-watching.

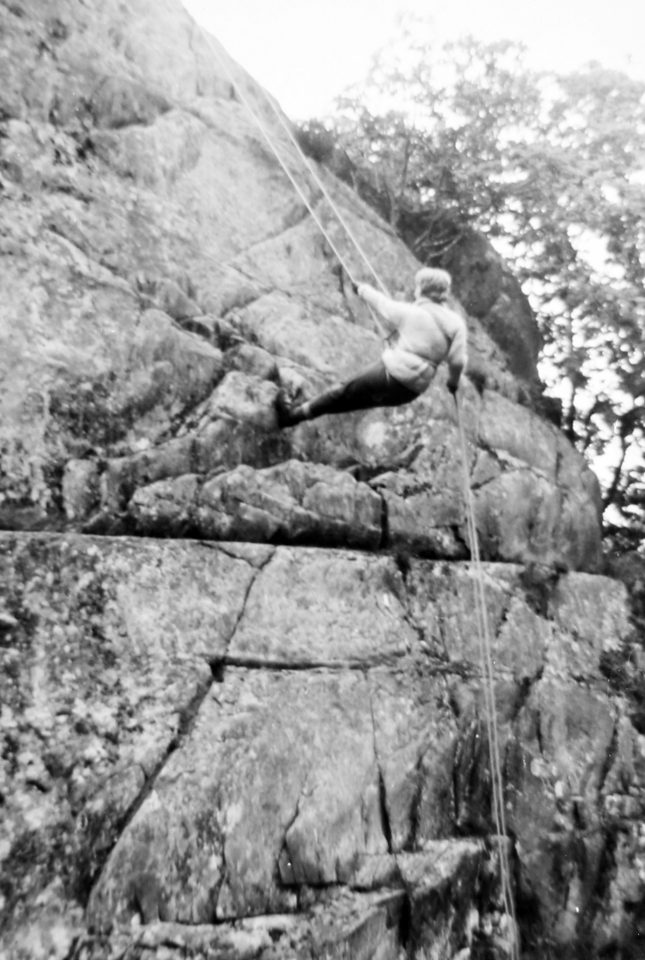

I moved to work at TI, in a central department, not one of the factories, at the Group Training Centre, at Woodbourne Grange in Edgbaston, covering all the TI companies. It was a big group then, covering about 60,000 staff in the UK, including many in Oldbury. We ran all the training courses there. It had a residential block at the back. TI bought this place in Wales, Plas, as an adventure centre, to encourage young people. The Industrial Training Act of 1964 came in and they saw it as an opportunity to maximise potential. We had great fun up there but it had a serious purpose. The guy who ran it, Harry Hughes, had this concept that if you could took a group of young people from the factory floor and offices, preferably mixed, take them out there, canoeing, mountain walking, rock climbing and relate the safety issues to safety on the factory floor you might make more progress than trying to give them a dull lecture on their induction. Even senior management would go up there and be put through their paces. We used to go up every weekend to help and work like mad. We’d set off on a walk, clambering up Snowden or something, Alan the warden Alan would say, Always remember when we are on these expeditions, we always go according to the slowest member of the group, that’s Pat over there. ”

Notes:

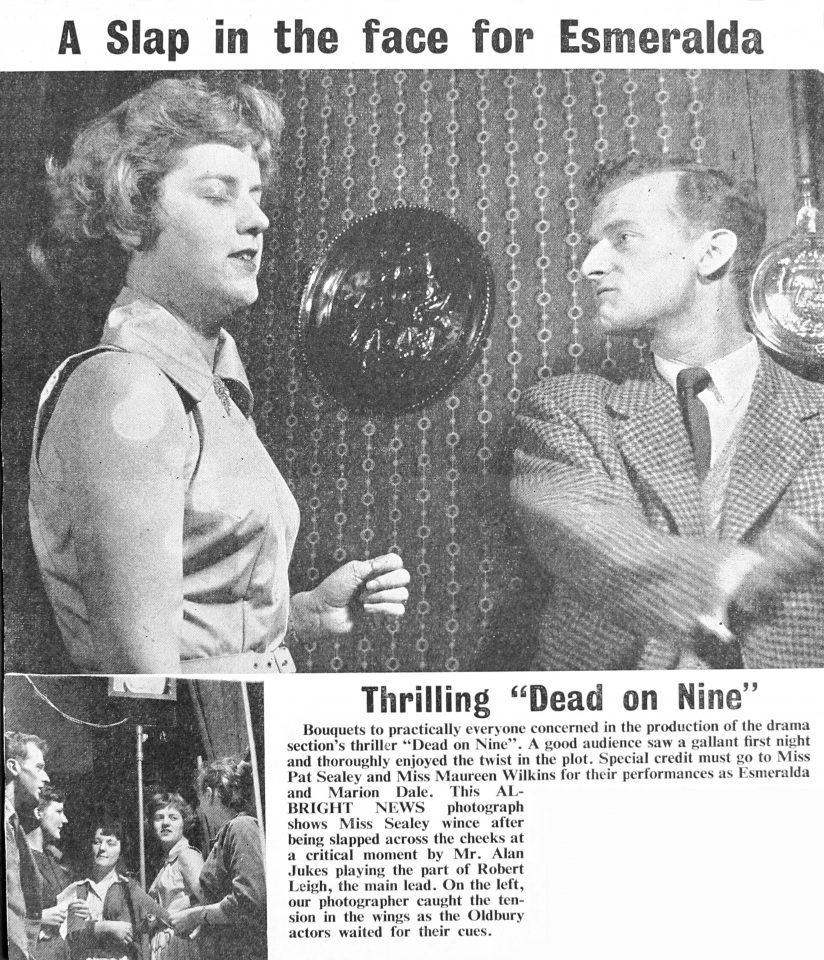

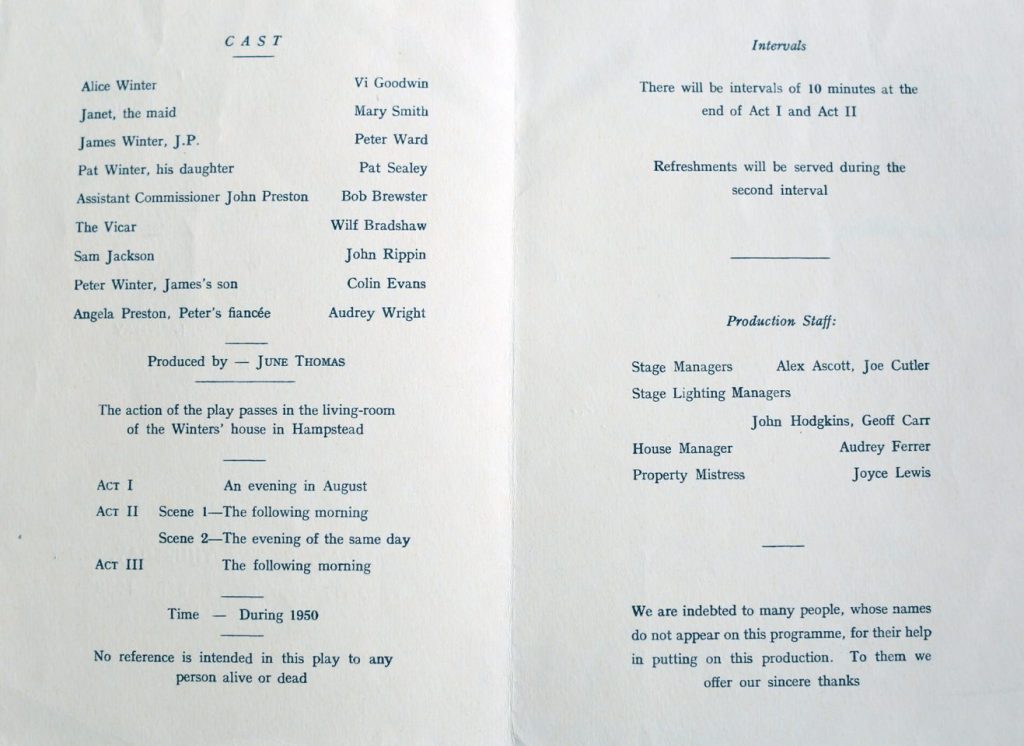

The dramatic group at A&W put on plays such as ‘Dead on Nine’ by Jack Popplewell, a 1956 play, performed in Oldbury in 1959. The settings of these plays were usually a living room in a country cottage, in this example the plot being: ‘A man reliant on wife's money asks for divorce after ten years of marriage, on refusal he attempts to kill her, and other murders ensue...’

As one of their play programmes of January 1958 explained: ‘The Dramatic Section meet once a month, between productions, for Play Reading. New members can be sure of a warm welcome and should contact DOREEN NURSE (Ext. 337), the Section’s Hon. Secretary.’

In 1956 the government closed the National Service Hostel at Causeway Green, which housed workers from Jamaica, Poland, Latvia, Czechoslovakia, Italy and the Ukraine, as well as from many parts of Britain. Many of the men there worked at Albright and Wilson, so the company decided to purchase the Sycamore Inn in Langley, opening it as a new hostel to accommodate 112 men.