Kelvin Atkins was born in 1948 and worked at Holden and Hayes in Bridge Street, Oldbury.

“I started work at 15, at Smiths, another Oldbury firm. Where the Asda is now, past Junction 2, Titford Road, there was a big wood place down there who made packing cases and the big reels that carry cables on the roads. That was my first job, making them. I started work at 4 pounds, 18 shilling and 6 pence a week - in the old money. But when I went to Drop Forge I was getting 12 pounds a week - which was a lot of money, but I needed it as I was living on my own. I was in care for three years from twelve, then fostered out.

It was where the money was; the harder the job, the more money. Obviously, you went for the money. My mate was an apprentice at 3 pounds a week, but I was earning four times the amount he was getting, but I needed every penny as I was living in digs.

I was born in Smethwick, off Spon Lane - Dawlish Cottages, Railway Terrace, George Street - it was actually a prefab that was plonked down where a row of houses had been destroyed by bombs in the war. There were stables at the bottom of our house and they used to take the horses down to the canal to pull the barges. By the stables, Mrs Habley lived there, used to give us some mint and rhubarb out of her garden, if you could call it a garden, more of a yard.

The Chances glass factory was over the back. The other side of the canal was West Brom. There used to be an old stack we’d climb, near where the tramway was, we used to climb that, a big water tankful of fish. Our prefab was by the railway lines. When the trains went through, ours used to shake. We used to go down through a gap in the fence and jump in the trucks, which had sand for Chances parked in the siding there. The next line was the mainline and the steam trains would come through at about 90 miles an hour - the non-stop ones. You’d stand up and the wind would knock you over and you’d fall back in the sand. We used to go down the canal and jump in the barges to play. From the canal side, which is under the motorway now, you used to be able to see into the works and all the furnaces; it was fascinating for us kids to see.

At the top of George Street was a Spring Works and they made the big coil springs for the suspension on the rail wagons. They’d draw the long bars out the furnace and wind them round. We’d be standing as close as you and they’d tell us, ‘Stand back, you’re going to get burned.’ There was no health and safety then.

They was different times then. It’s hard to describe really, you didn’t have a lot but you were happy with what you’d got. People have got what they want now, not what they need; you had what you needed then and you were lucky to have what you needed basically

I left school on Friday and started work on Monday, I was living in Richmond Hill, Langley, a boarding house run by Mrs Dillon, where my brother was also living. My mom worked at Accles to start, then at Albrights, making phosphorus bombs, then she came to Holden and Hayes. My brother joined as well. It was a family kind of business, everyone had a friend or relation there, that’s how it worked.

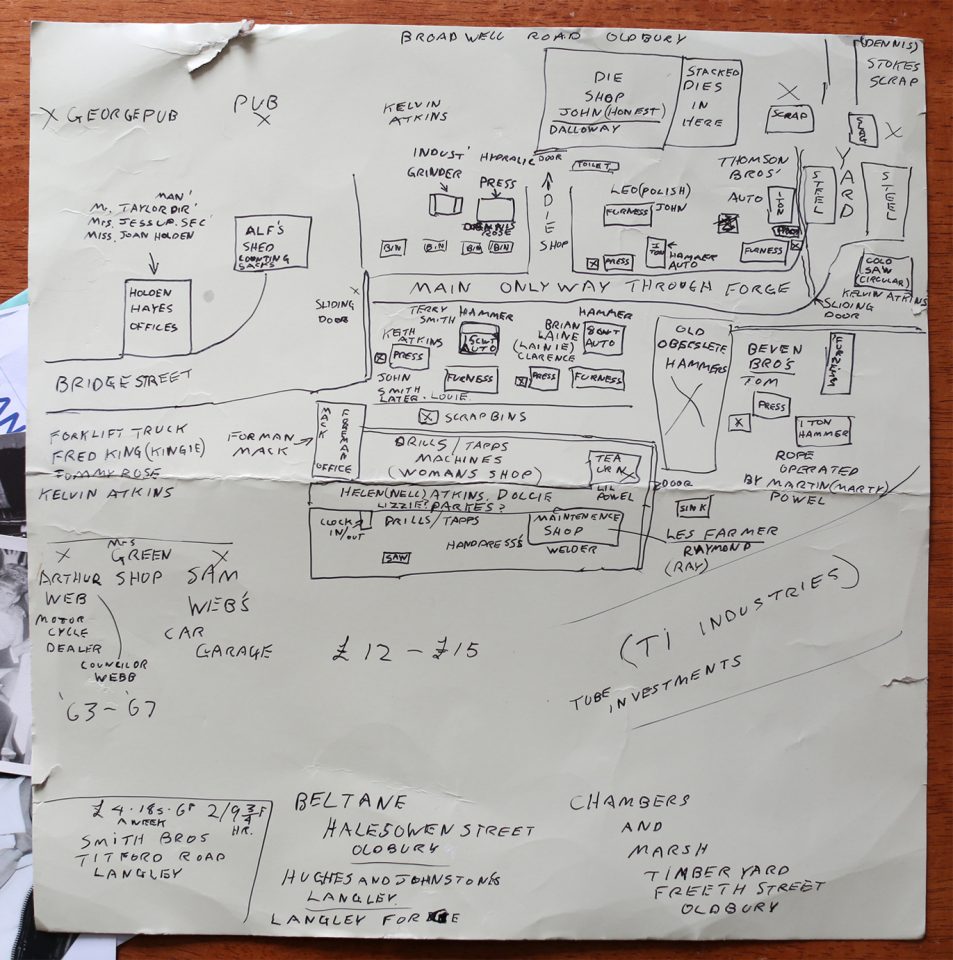

Their office was in a house on Bridge Street. In the main forge, the actual road through was about 8 foot, it went all the way through the forge to the yard, where they stored the steel and scrap and the slag off the stampings. There were 3 one-ton hammers, one fifteen-hundred weight hammer and one eight-hundred weight hammer. There had a lot of old ones there that never worked, metal banded, very early ones. The newer ones were Massey hammers with big nylon; some hammers were automatic, some were rope driven depending on the job.

I started on the grinder, just inside the main forge, a big double wheeled grinder. I spent the first six months grinding the burrs off stampings. All I had was a mask and a bottle of milk every day. You made an apron out of a sack and had a pair of gloves; you needed gloves otherwise your hands would be shredded in no time. The stampers didn’t wear gloves because of the heat - it was hot in there, they were facing the furnaces.

You could be out in the rain absolutely soaked and stand in front of that furnace and in less than two or three minutes you’d be bone dry, that’s the heat they gave off. The stampers used to pour sweat off them. They just used to wear a shirt and trousers. They didn’t have any goggles, no glasses, no helmets, nothing. It was what it was. If things were flying about they’d just put their hands up. Burns was common. Cuts, burns, bruises were part of it. The first aid box was a little box in the die shop, a few plasters and bandages and burn cream; that’s all they carried. Anything serious and you’d be up the hospital, but I can’t remember a bad accident there. It was a happy time. I know it was hard work, but you had some good times. They’d go straight to the pub from work and have a couple pints before going home. They’d sweat that much they’d take salt tablets. It was hot in there, especially by the furnace.

These blokes worked hard, because they were actually handling the steel. At Langley Forge, where I went later, though they worked with heavier metal, it was that heavy cranes picked it up. It still hot, the heat was terrible in Langley Forge, a lot more than the drop forges because of the size of the ingots, though they’d not doing the mauling they do in the forges. In the forges you’re working with the metal, picking it up.

My dad was a moulder at Birmid, pouring the metal; he used to come home as black as the ace of spades. The foundry is dirtier, but for actual sweat and graft the drop forge is a lot harder work physically. Heat wise they ain’t a lot in it; they’re hot industries.

There were all sorts, quiet blokes and the other end of the scale. They’d grab hold of you, some of them, and hold you in front of the furnace till your clothes would start to burn and your skin touching. I used to wear me boots laced up. I hadn’t got steel toe protectors, which you were supposed to wear. The stampers never laced theirs and I found out why. I had some scale go down me boots the once and by the time I got my boot off when I pulled my sock up it took the skin off with it. The scale had gone down hot and stuck the sock to my skin. That’s why they left them loose, so if anything went down they could get their boots off quick.

What they’d do as well, they’d bring bacon from home and get a big flat piece of metal about 6 inches wide. You’ve heard of doing it on a shovel, they didn’t bother with the shovel, they’d shove the egg and bacon on and shove it in the furnace for half a minute or less. It was sizzling and they’d put it on the bread and eat it. It was a different way of life then.

The TI was at the back of us, as you go down the end of Bridge Street. On Broadwell Road was an old archway and that was the back entrance into the forge. There were some car garages and a Jamaican family lived there. Stokes Scrap from Great Bridge would come and fetch the scrap twice a week. There was one, called Donald, whose trousers were that shiny with grease and dirt, they actually shone they did. They were twice the weight, full of the oil. In his back pocket he always had a big wallet thick of notes. He always had loads of money on him.

I was on 12 pound a week and it went up to 15. My mom was on 15 – 20 pound a week. The stampers were on about 40 pound a week; they could run cars and have houses with that sort of money then.

The British Rail lorries would come in the yard with the steel bars, up to forty foot long, bringing them off the railway. They’d be put on a stacker truck and we put a chain on the back of it and drag them through the forge on a bogie. The long lengths were loose on the railway lines but the shorter bundles of 6-8 foot long would come with wire wrapped round, knotted with heavy wire tied up at either end. They’d paint the end to colour code them, red and green, or half and half on a bar, then you’d know what it was.

Mac, the foreman, he’d get a piece of metal and grind it, because it was dark in the forge - there was light but it was mostly very dark. As he ground it, the sparks would come off and the colour of the sparks would tell him what type of the metal it was, as there was different steel for different applications.

Everybody was hands-on, there were no passengers. Everybody had a job and you did it, even the gaffers. Our manager, Mr Montgomery, was a working manager. He didn’t have to be, he could have sat in the office if he wanted, but he wasn’t that kind of bloke. He would get on the grinder in his suit. He didn’t even put on an apron. If you had to turn the work out, he’d do it. The firm was flourishing, so they started two shifts, six to two and two to ten.

You did what you did, things were as they was. There were unwritten rules in these places. You soon got into the run of the place, like being in the army I suppose, in a sense. Everything run like clockwork. Everybody knew the place, knew the job basically. If the hammer broke, Mac would be there covered in oil and grease, mending it if he could. There was a lot of smoke in the forge and noise and the banging and all that. The neighbours used to moan about the noise and all the crashing and banging. They wanted them closed down.

On every hammer there was two workers, and on the rope hammer there was a driver as well, so that’s three on that one. Because there was a double shift you can double up that number up. There were no more than 15-20 women in the shop and in the machine die shop, maybe 10 making the dies for the shapes. Lil used to make the tea, and her son Martin used to drive the hammer.

As I was 15, they’d send me up to Chambers and Marsh, where the council offices are now, to fetch big bags of sawdust on my bike. I’d put three bags on the rack of my bike and I’d come through Oldbury town with the front wheels up in the air because of the weight at the back.

What they used it for was, as the hammer was coming down, they’d throw some sawdust on. They only did this on what they called the billet jobs, the small pieces. They’d throw it on and as the hammer hit the metal the sawdust would explode and come out like gunpowder, and it would expand the metal. They’d got a wooden stick and an oil tin, and they’d stick the wood in the oil and flick it on the die at the top and the bottom and that would stop the metal sticking.

It was a tough hard job, but it was a fraternity. You’d have a laugh. Something would go wrong and it wouldn’t be necessarily funny but everybody would find it funny. Somebody got hurt, they knew they weren’t hurt bad, so if somebody did something stupid and then got hurt everybody would laugh.

There were some characters in that place. There was Kingy, a stack truck driver, he had a beard like Desparate Dan out the comic. I’d only be there a few days and he grabbed hold of me and rubbed my face. I’d only just started shaving and my face came out in a terrible rash. That was a joke like. They send you for a rubber spanner or rubber hammer to make you look saft, but you only fall for that once.

Les was a maintenance bloke. He used to work on the hammers. What happened to him was - why he come off the hammers - when they work the steel down, when you start off its a long bar and you have to use a pair of tongs to hold the bar. As you work it down it’s getting colder - when it comes out the furnace it’s a yellow heat, it looks lighter when it’s hot but it ay. But as you work the bar down to nothing and you’re grabbing it with the tongs, he caught the end of the tongs under the hammer as the hammer come down; they hit the tongs and they shot back and went right through his leg. He showed me the scar. It was like a bullet hole here and a bullet hole there. The handle of the tongues, which are about as fat as a finger at the end, they shot right through his leg. That’s why he come off the hammers.

One day, me and my mate Louis had a fight in the forge, under the furnace, over an unpaid bet. We were nearly sacked over that. I paid him when I lost, but when it was his turn to pay me months later he never paid me. It caused bad feeling. We had words in the forge. Next thing you know, I said ‘I’ll see you outside’ - which meant we’ll sort it in the yard. He turned round and he nutted me straight in the nose. I grabbed hold of him and we started wrestling on the floor. I got the worst of it. We were under the furnace and of course there’s molten metal coming out of the furnace, not all the while but it can come out at any time. They dragged us out and told us if we didn’t stop we’d be both up the road. I wasn’t really a betting person, but we used to go in the foreman’s office for breakfast sometimes and we’d have some crazy bet and put a couple of bob on.

Then I worked a year on cutting steel billets. You had to weigh it, take it to the scales to check you’d got the right cut. Dennis’s son, Trevor, was a stacker truck driver. As he was coming out the forge, there was a big girder across. Because the sun was in your eyes, it was black when you came out the forge because your eyes took time to adjust. As he come down, he forgot to lower the forks and he hit the girder with the forks. The girder come right down on him. It snapped on the one end and come down like a guillotine across the top of the truck and caught his shoulder. It didn’t hurt him bad, but he was going to be off for a few weeks. Actually, he never came back. They had nobody to drive the stacker truck.

I used to go and empty all the scrap from the night shift and bring fresh bins in, so I’d taught myself to drive a stacker truck. You learned on the job. In them days, you took the job on a Monday and if you were no good you’d be up the road by Friday. You learnt the job in a week or you were up the road. You got better at it, but if you couldn’t do the job in the week, you’d get the sack.

It wasn’t just sitting on a truck. You’d unload the wagons of steel on the bogie, you’d empty the bins full of stampings, you’d empty the scrap bins where they’d guillotined the metal off after they’d made the stamping under the press. After you did all that you’d be shovelling scale up – it’s metal but like black powdery flaky stuff and that piles up.

Lorries would come in to fetch stuff to be shot-blasted, lorries come in fetching stuff, lorries taking stuff, sometimes you never got a break from the time you got on your truck. It wasn’t always like that. Some days you might have time to walk up the shop in five and get yourself a bottle of milk or some fruit. Mrs Green did a roaring trade on the corner. I’d get a bottle of Channel Islands milk, Gold Top. I can’t stand it now, but I’d at the time I’d drink a bottle of that and have an apple or orange.

My mom got the sack. She worked in the machine shop, on the twilight shift, finishing at 10 at night. There was no gaffers about on that shift. What she’d do was, she speeded the drill up, being on piece work, get the job done quick and finish an hour and a half early and get someone to stay there to clock her out. Her and her mate Dolcie went home early, but there was a miserable sod who was a bit jealous and told on her. They were called into the office and they thought they were going to get a raise but instead they said to them ‘Here’s your cards’ and they got the sack.

My brother went to Hughes and Johnson and when I left he said, come to work at our place. I went to Hughes and Johnsons and did a day there and said, ‘No, I don’t like it.’ It was like the Black Hole of Calcutta. It was rough, no washing facilities, nothing there. Like going back in time. Holden and Hayes was rudimentary but this was even worse. I walked in and walked out, just did a day. It embarrassed my brother, having got me the job.

When I left I tried a job as a salesman for a week. That was a waste of time. Walked my legs off and made one sale, for a Caxton’s Encyclopedia. I went on to work in sheet metal work, making it and fitting it, but that’s a different story altogether.”