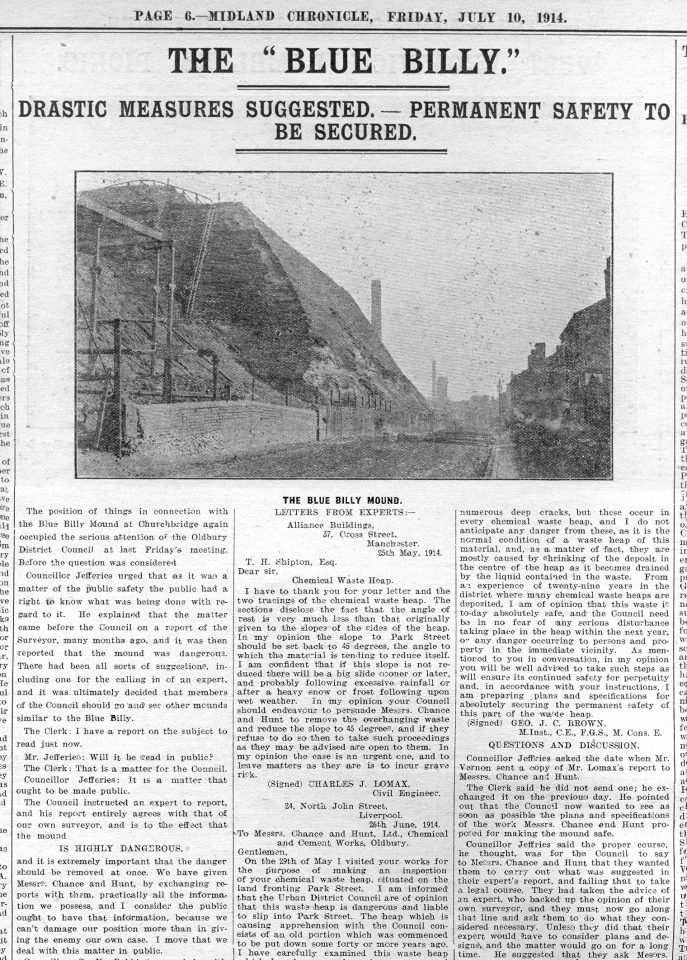

The ‘Blue Billy’ was the local name given to a large mound of both mining and chemical waste. At the two nearby chemical works owned by Albright and Wilson and Chances' a process for the making of salt-cake produced large amounts of white waste material, calcium sulphate. In its contaminated form, as calcium sulphate, it forms a blue-grey ash, which constituted the main body of the ‘Blue Billy’.

Pollution from industrial waste was a common feature of the landscape. Back in 1864, the authors of ‘England’s Workshops’ (Thomas Archer, W.B. Teqetmeier and W.J. Prowse), described Oldbury in the following text:

‘The approach to Oldbury is marked by a heavy pall of smoke which, hanging over the whole tract of the country, shrouds nature in a dun eclipse. Amidst an undefinable labyrinth of pit banks and hillocks, mounds of cinder, craggy masses of clinker, often lighted by a lurid glare into strange and fitful shape, rise the more regular forms of innumerable shafts, kilns, tall, pyramidal blast-furnaces, and strange uncouth machinery. Crowded together amidst this volcanic waste, as though separated for ever from the life of villages and country homesteads, lie the pitbanks, the collieries, the forges, the works for iron and steel and gas, tin and tar, copper, oil, and lead, the soaperies, the distilleries, the potteries, and, as it seems, a hundred others, for supplying the world with material which has become a second nature wrung from the necessities of the first. Here, amidst din and clangour, rises the hot breath of a thousand forges, the heayy vapour of brick and lime-kilns, the black and choking smoke of mighty fires, all mingling in one great, black, boding cloud which broods immovable above the earth. to the realms of chemical manufacture, we pass between glittering cliffs which change their hues as we proceed, from pearl white to shimmering sea-green - see masses of green stalactites heaped here and there - stop before the sheen of crystals - walk upon snow-pure sands - gaze, wonderingly, at hillocks of red, and brown, and black, and brilliant colours, amidst which rise two gigantic chimneys and a score of towers. It is in the main road through the works, and amidst the continuous passage of horses and waggons conveying the various materials from the waterside to their fiery destination, that we become conscious of the word “salt,” upon which, collecting our somewhat scattered senses, we say, “Indeed!” and, at once becoming prosaic, learn that this article, of which the white cliffs beside us represent some hundreds of tons, is necessary for the manufacture of sulphate of soda. At the base of the great chimney lie the various apparatus for condensing hydrochloric add; and, crossing the canal which runs through the centre of the works, we see, arranged upon its wharf, row after row of glass and gutta-percha carboys ready to be filled with the different acids now in course of manufacture.’

Paul Prescott recalls:

“There were two distinct areas: the Blue Billies on the Oldbury town side of Park Lane, and the Billy Banks (pronounced, of course, ‘bonks’) on the Langley side. The Billy Banks were green and grassy and, as far as I know perfectly safe and pleasant. The Blue Billies were blue-grey in colour from the chemical waste, with little pools of noxious liquids. As kids, we used to play regularly on the Billy Banks, but only occasionally on the Blue Billies, not least because you had to get through a fence to get at them. I shudder to think of the potential consequences, but I’m still alive.”

Bill Parkes recalls:

“Blue Billy was two pools. If you go down to the motorway island and look across left, it’s a trading estate now. That used to be two big pools where they used to pump all the acid water and the alkaline, everything the factories didn’t want went in there. Every time you went it was a different colour. That was levelled off eventually, but was the reason it used to flood, the clay pits here, the mounds, wouldn’t let the water away, and the drains at that time weren’t capable of doing anything with it. So it would flood.”

The mound was finally removed in the mid 1960s to make way for the M5 motorway. The motorway from Quinton to the A4123 was opened in May 1970. The section from Park Street, 3.6 miles, was built by Christiani-Shand in a £5.8 million project which took two and a half years. Eight new bridges were required, Titford Pool had to be spanned on 50ft deep piles, and the Blue Billy had to be removed. The contract for removing the chemical waste, transporting it across Birchfield Lane and filling the marl holes went to Richardson Brothers. It proved to be a major undertaking.