Dr Terry Daniels has spent all his working life in Oldbury. He is chair of Langley Local History Society, Oldbury Local History Group. Writing and lecturing on the history of the area, he has produced a number of books and runs the website www.historyofoldbury.co.uk

“I was born in Hallam Hospital in West Bromwich but my parents lived in Langley, behind the Hen & Chickens in Parkfield Road. So I am a Langley-Oldbury lad. When I got married our first house was in Oldbury, but we then defected just over the border into West Smethwick; you can see Oldbury from it, so I still feel at home.

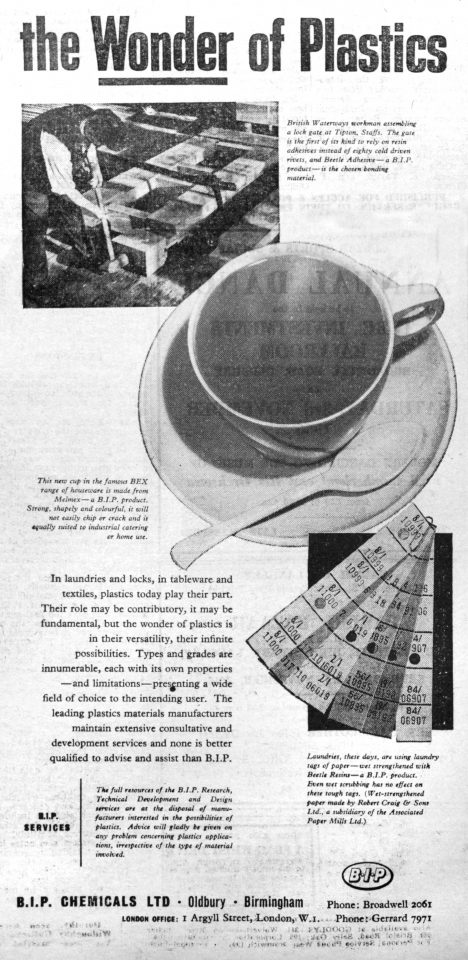

I went straight to British Industrial Chemicals after getting my PhD at Birmingham, where I had studied polymer chemistry, so to go into the plastics industry was a natural really. I started work in the labs as a reasonably junior member of the laboratories there.

In those days the labs were quite extensive and work being done on the development of certain plastics, which really didn’t come to very much in the end, but it was great work there. It was a very relaxed sort of atmosphere at that time. I was just too late for the rounds of jam sandwiches, which they previously had - very, very different from industry today. A lady came round mornings and afternoons and offered jam sandwiches to the people working in the labs and offices. That had just finished before I went, but it was still very relaxed, a very friendly sort of atmosphere. Those were the days I suppose that, like most industries in the 1960s, we hadn’t really been taken over by the accountants. Although the bottom line was important, the company was being run by engineers and chemists, people who understood the products in great detail. I gradually witnessed the change from the scientists running BIP to the accountants running it: that really changed the atmosphere over the next twenty years or so, when everything was based on getting the required bottom line. It was still a great place to work, I had great fun.

I moved out of the laboratories eventually and took a more general management role in the engineering thermoplastics section, and ended my career doing that side of things. I was a technical officer when I first started at BIP, and it was a great day when I was promoted to senior technical officer. I was working in the laboratory studying the degradation of a product we were trying to develop, which was a polyformaldehyde. There was a small pilot plant producing this material and we were trying to provide something to rival the producers of acetal* like DuPont. We had a product that was reasonably successful, but its degradation was a problem and we were trying to reduce that. It was a specialist thermoplastic that would be used in ordinary everyday objects. We never actually produced it commercially in the end.

I came in part of the way through the project, working on it for a year or eighteen months before the plug was pulled on this particular material. I ended up in a new department, the New Products Group; we were looking fundamentally at anything we could make to supplement the products that BIP already had. BIP produced amino plastics, which were thermosetting materials and couldn’t be recycled other than grinding them up and using them as a powder. That was a problem because the great rivals, the ‘newcomers in the block’, were thermoplastics These could be recycled, remelted and remoulded if needs be. We didn’t have any products in that area. Our thermosetting business was still good but could see it beginning to decline as thermoplastics took over. So we were looking for new products we could have to replace some of the business that we knew we were going to lose. Thermosetting materials went into things like the old decorative bottle caps on medicine and scent bottles, into ‘melamine’ tableware, and, a big seller, into toilet seats, which always amuses people. Everyone’s ‘avocado’ or ‘aqua’ toilet seat in the 1960s and 1970s would have been made in BIP Beetle products.

Our brief was to find something to replace it, and eventually we got involved the production of Nylon 6. We licensed a plant that was meant to produce Nylon 6 itself, but we could never get it to work as intended. The whole economics of the process was based on recovering some of the starting material to reuse it, and that part of the process never worked satisfactorily. We ran it for a while, but eventually closed it down as being unprofitable. We then bought in the base nylon and compounded it, putting pigments in to colour it and various other additives to produce a whole range of nylon thermoplastics. I was heavily involved in the scientific side of the developing the materials before I moved over to the management side of the business.

The building burned down three or four years ago, so the plant that we had has totally disappeared – so all my industrial heritage has gone.

BIP had invented ‘aminoplastics’ in the 1920s, and they were the largest manufacturer of them world-wide for most of the 20th century. The great advantage of aminoplastics was that the resin that they made, from which the moulding materials was developed, was water white. The main competition back in the 1920s and 1930s was phenolic resin, which was brown in colour. So you could have any colour in phenolics as long it was black or dark maroon or brown, that was about the limit. The products that BIP came along with were pure white so you could have them in any colour by adding pigments to them.

By the time I joined the company in the 1960s, they had built up such a range of colours across the years that there were literally thousands and thousands of colours. And it was a great skill to be able to make sure if we produced a shade of pink one day it was exactly the same pink the next time we make it. So the colour matching of these materials was a critical part of the process. Roger Best, when I was there, was the guy who was leading the colour matching side. The operators would come up with a little sample of the powder and a moulding from it and show it to Roger. He’d look at it carefully and say, ‘Oh we need that amount of this colour to get it absolutely right.’ It was a very skilful job, and in the good old days, it was done by eye and experience; nowadays they have instruments for doing this. It was a critical part of our process and one of our specialities and guarantees; that we could make any colour in the material and guarantee that it would be consistent.

I started at BIP in 1967, when I was 24, and worked there until I was 52. Then BIP was sold by the T&N Group to a venture capital group, and the arrangement was that the new company could offer members of staff early retirement on a reasonably favourable terms. So they came round and asked who would like to volunteer for redundancy. I didn’t do anything about it then. They came around six months later, after they didn’t get enough people on the first trawl, and by then I was getting fed up with the new regime. So I took early retirement.

I was looking for things to do then, so one Christmas sat down and started to draw up the family tree. I got interested in genealogy and started to research my family history. My relatives on my father’s side had lived in Oldbury for a century, so I tried to put them in their social context and that’s how I got involved in Oldbury’s local history.”

Note:

*Acetal (or ‘polyformaldehyde’) resin is a highly crystalline engineering thermoplastic used in gears, safety restraints, door systems, conveyor belts, healthcare delivery devices and other components.