Percy Eamus was born in Blackheath. He served an apprenticeship at the electrical engineering business of British Thomson-Houston (BTH) and then worked at Accles and Pollock. He later went into management.

“People don't realise how much that this area contributed to the economy and the social fabric of the country, and Oldbury in particular - the breadth and depth of industry here was a great example of that. Even locally now, people don't know enough about this history.

Where I grew up, at the bottom of our garden, over the unadopted lane we used to call it Back Lane, there was a clapboard shack and every year it seemed a bit lower as the bottom boards rotted away. There was a bloke named Jesse Parsons lived there and he had an orchard and he used to sell fruit from that. Every now and again, if he was short of money, he would buy a burnt out lorry and use the chassis to construct a caravan on spec, which he would then sell. That guy had apparently invented, if invented is the word, the sunshine roof for cars. He was pally with Herbert Austin, later Lord Austin. At some point he went to America in the 1930s to make his fortune, so he got a letter of introduction from Lord Austin to Henry Ford. He got on famously for a year or so, then he decided Ford had taken advantage of what we would now call his intellectual property and took America’s biggest venture capitalist to an American court as a Limey. He came back a poorer but wiser man.

I remember going to Sunday school at a Methodist chapel, and over the road in the villa houses there was a big gate that opened up onto an entry; you could get a lorry up and at the back was a forge, where they were making manacles and mantraps. Next to our house was a big brick built building, and there was a machine shop. You’d be in the garden and the walls were throbbing and shaking about and there were these plates where wall together. Opposite was a very big garage and in that was a forge and a furnace where they stamped out the components, which they machined and then sent them on. It was remarkable the amount of back yard activity there was.

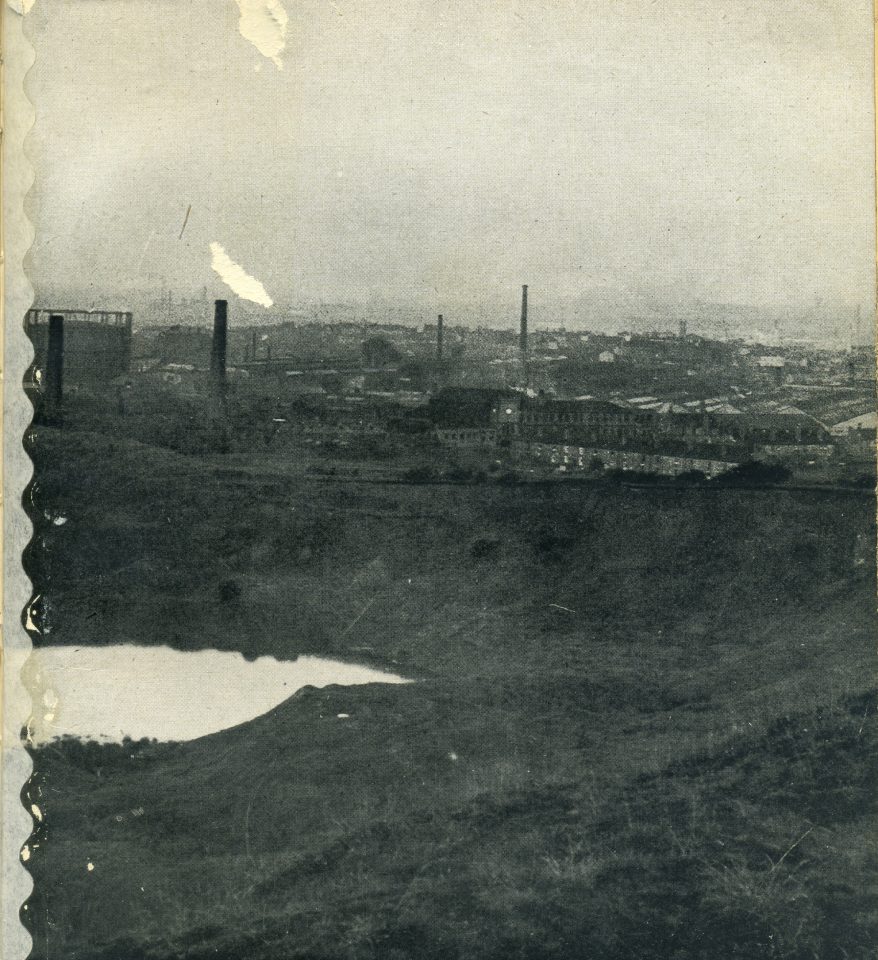

There had been a lot more trees before the war, but a lot of them were cut down and used for fuel. In 1948, when we had that big winter, where I lived you could walk down through some fields to the canal and there were pit banks that were grown over; people were mining into there to dig out what we called ‘nutty slack’ – it would burn sufficiently. How people weren’t killed I don’t know, as they went in quite deep. There was an outlet there from the nut and bolt factory and the pipe had broken open and you used to get untreated sludge from the machining operations forming pools and puddles or rivulets. There was a structure over the top of old pit and we used to love throwing a brick over it and counting how long before you heard it go splash. That’s what finished the pits here - they were all wet pits.

My mother used to talk about getting a tram to Kinver when she was a kid. We never had family holidays as such. We went to Scarborough for a week when some relatives came over from the States, when I was 17, which I paid for myself.

There were characters about. My uncle Albert was like the scribe of the family. If anyone needed a letter that had any legal aspect about it, he would write that for them. He could do a Scottish sword dance. He was in the Cameron Highlanders in the 1920s and 1930s. He’d been in Hong Kong. They used to go on deep patrol into China, to keep and eye on what the warlords were up to. He’d swum in Hong Kong harbour. The international aspects of the Black Country are far deeper than people realise. He was quite a skilled man, a gauge-maker, which involved making little blocks of metal you could check the accuracy of micrometers against. So he’d hone these down and knew enough to work out what size they’d be after being heat-treated.

Before I left school I had a part-time job at a butchers for a couple of years, where he did his own slaughtering. I never once saw an act of cruelty there. It was done very humanely, very cleanly and very professionally, When I left school I became an apprentice maintenance electrician. I was late learning to read and I listened to the radio a lot. My reasoning, which was a bit ahead of my time, was that I got it into my head that automation would be a very important thing in the future. So I thought, with automation, there would be more work for people who maintained the equipment. So my logic was to get into an area where the skills would not become redundant.

I had a very good apprenticeship at BTH. We used to have unofficial extensive lunch breaks and tea breaks, but what you learned in those breaks was amazing. There’d be some 20 electricians and the range of experiences they’d got, well I learnt a lot about life from their experience. There was always somebody there who could illuminate whatever the discussion was. It was, in the sense of learning about life, as good as any university.

It’s remarkable how much industry has gone from round here and so quickly. I put a lot of that down to North Sea oil myself, where they diverted all that investment elsewhere in the 1970s, which did not go into local industry. In the days when there were these large factories about, down at Broadwell there was a lot of events on at the club down there, quite a massive centre, dances and so for that the TI Ballroom. When I had the apprenticeship at the BTH in the canteen we had a stage. I gave a hand for a couple of years, helping with the scenery. We did Oklahoma, South Pacific, good quality musicals. My brother was a violinist and although he didn’t work for Belgrave Engineering, they had an orchestra and he got involved with that. It illustrates the sort of thing that went on in factories in the Black Country. There was a lot more with these industries and factories that meets the eye, and with the passage of generally large units and all that went with there’s a lot gone out of the social life.

I had an ambition. I decided what I’d like to do was become a works engineer - that is, a maintenance manager. That means I’d be doing electrical and mechanical, so I was looking for a job which would be a bridge between the two. I’d spent some time in the calibration department during my apprenticeship on a range of instrumentation - nothing like today’s instruments. I decided by getting into that would broaden out my base and make me more credible. I saw this advert for a Pyrometry Technician at Accles and Pollock. We had a few at BTH, not many, but they worked on the same principles of the instrumentation that I did know. I had an interview and I was taken on. I met my wife there. She was from McKean Road. I met her at Birchley Social Club. We got married in Oldbury Church.

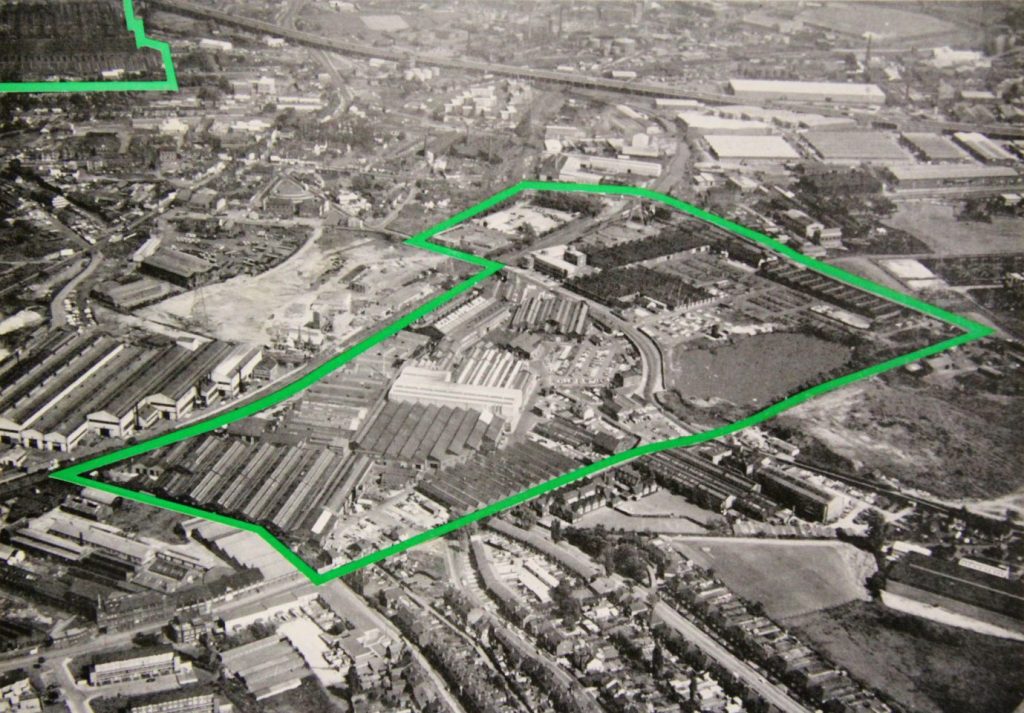

So I was working measuring the temperature in furnaces, for example doing surveys of the hearth temperature when they were doing aircraft quality tubes. You’d have a print out of that, to be recorded against with that batch, so if there were any future problems we could trace back to the heat treatment it was given at the time it was manufactured. I went there when I was about 21, in 1964. I’d got my instrumentation laboratory - that’s a posh sounding name isn’t it? - it was actually a partitioned off area in the corner of the mill office down at Broadwell. The bloke that eventually became my father-in-law occupied the desk just outside. Before that he’d been the supervisor of the Hypodermic Department. He had what used to be called a nervous breakdown in those days, which he put down to managing a lot of women, but we’re all entitled to our own prejudices.

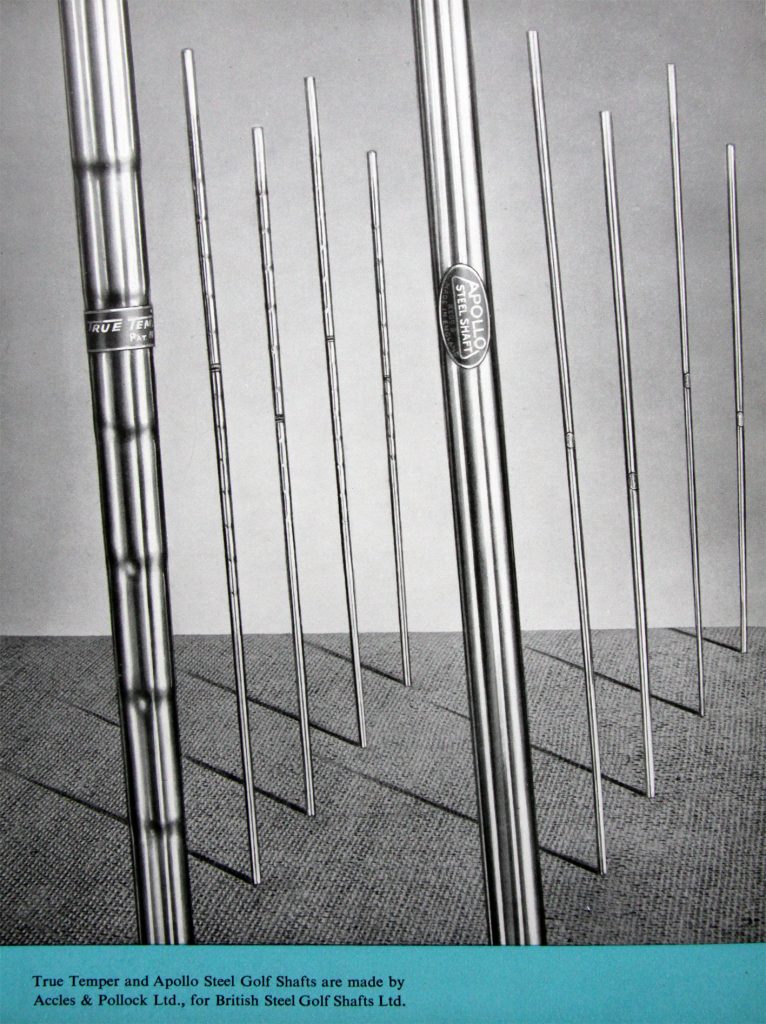

When I think of the things they did there at the factory. You had the Sporting Goods Department; they made bows, javelins, golf shafts - that was a weird looking process, the golf shafts. They’d got some glass tubes with some chemical to do one effect on the tube, bubbles coming up for that, green like. It looked quite science fictiony.

When the TI group set up a separate stainless division over Walsall, I think that took the heart out of Accles. I often wonder if taking out the stainless, being such a very profitable part of the business, left Accles very exposed in the area they were left with, unbalancing the business. I certainly saw that later with other firms I worked with in the area. There was one firm that was part of a bigger group and it reached a point where the metal we were buying from our own group - from the rods division over in West Bromwich – cost us more than the fully finished products that our customers could get from Italy, stamped, machined, passavated, weight for weight; cheaper than we could buy from our own group that made the rod in the first place. I don’t know what kind of economics that was. That really was ridiculous. I didn’t have much confidence in management in the 1970s. Clever book keeping, essentially, featherbedding one part of the company to expense of another part.

When I was a student of management one of the lecturers I had was an accountant who had worked for that rods company and he explained they had to put a value down for their feedstock, which was a big pile of scrap brass, so they would stand there with the works manager, him and somebody else and look at it. The one would say, ‘Well I’d say it’s worth £900,000’ and the other would say, ‘No, more like £850,000’. How do you value something like that? Yet you have to put value on the books.

A lot of local companies were started by Quakers. They were very good firms. I worked for Robinsons, over Carters Green, not far away from Oldbury. They were a really good employer, and the Quaker principles were present in the business. Ted Heath had brought in this idea (in 1972) to curb inflation, where he got people to accept ‘threshold agreements’, where if the cost of living burst a certain point it would trigger a wage rise. I was called in for my annual salary review and the engineering director looked at his list and told me I’d get so and so rise and I asked, ‘Well the threshold agreement you’ve got with the clock workers, does that apply to staff?’ He said, ‘Well I suppose it does.’ End of interview, off I went. Come July, the threshold was triggered but there was nothing in my salary slip. I went to ask about this. The engineering director was on holiday so I saw his deputy, and he went to see Anthony Robinson, the manager of the plant, and on my word of what the that director had originally said to me, they gave me the rise and every other member of staff on the site. How often do you come across that situation?

I was never sporty, always been a bit political and spent most of my life as a bit of a student of management. I got a post-graduate qualification, in Industrial Management, from what was then Wolverhampton Polytechnic. I was offered a place on the Aston University MBA programme but unfortunately the fees were £5000 and to put that in perspective my mortgage was £3500 on a detached house with a plot of land. I tried to get the firm I was working for interested but they didn’t want to know; then the penny dropped, as the lease was up on the satellite factory where I was the maintenance manager so they weren’t looking to invest in anybody. They were looking to closing the place down and clear everybody out. So I was made redundant, but I ended up working as an agent for a French company based in Tours, owned by the Delta Group. I had to do a handwriting test for them. They later told me the analysis said I was ‘commercial’ - I wondered if they meant full of low cunning and devious. That was an interesting chapter of my life.”

In Oldbury it was made

Industrially the heart of the Nation,

From corn plasters to hypodermic tube,

From boilers to home detergents,

From sweets to crafted gin.

The home of the warlike sten gun,

The maltings for Banks’s brew,

On canal-side Thomas Clayton and foundries quite a few,

But also homespun people as varied as the view.

Brades’s tool and products,

And Chances glass to view,

And Chance & Hunts for chemicals to add to this great brew,

And malt as in the vinegar (or alegar to be true).

No end to its list of products,

Nothing that can’t be made,

The true wealth of our Nation,

Here were on parade.

Furniture from finest tubing,

And caps for nuclear fuel,

Plastic fixing chemicals

And tar distillery too.

This mix it called for talent,

And that’s what we should view,

The native wit and wisdom that made this witch’s brew,

It stood great stead in history and will in future too.

Pen nibs and sporting products,

The clothing for our kids,

I’m sure there’s much that’s missing,

In this great working list.

And at a personal level,

Much more was created here,

For love was made in Oldbury,

I miss my late Pauline.

Turned, drilled, welded, brazed, stamped, extruded, drawn, fabricated, cut, stitched, distilled, cooked, born, imagined, dried, retorted, annealed, passivated, printed, administered, innovated, extrapolated. Made in Oldbury? If not, it was not made. (OK, I exaggerate – just a little.)

– Percy Eamus, 2017.