Bryan Harris was born in Walton Road, Oldbury. He worked for Accles & Pollocks in the Maintenance Department.

“All my family lived in the Black Country. My mom and dad lived down Tat Bank. My mom’s parents had a boatyard down Oldbury – Pearsalls - and they had all the long boats carrying stuff around the country on the canals. We were very grateful to the boat people because they used to discard all the little lumps of coal and we used to go down on the side of the canal when we were kids, coal picking. Down by the Navigation Bridge, along there we’d pick the coal out the banks and off the side. That was the only fuel you could get to warm the house up.

You’d see the canal boats all down the side of Accles; they used to load all the stuff onto there, that was ever so convenient that was.

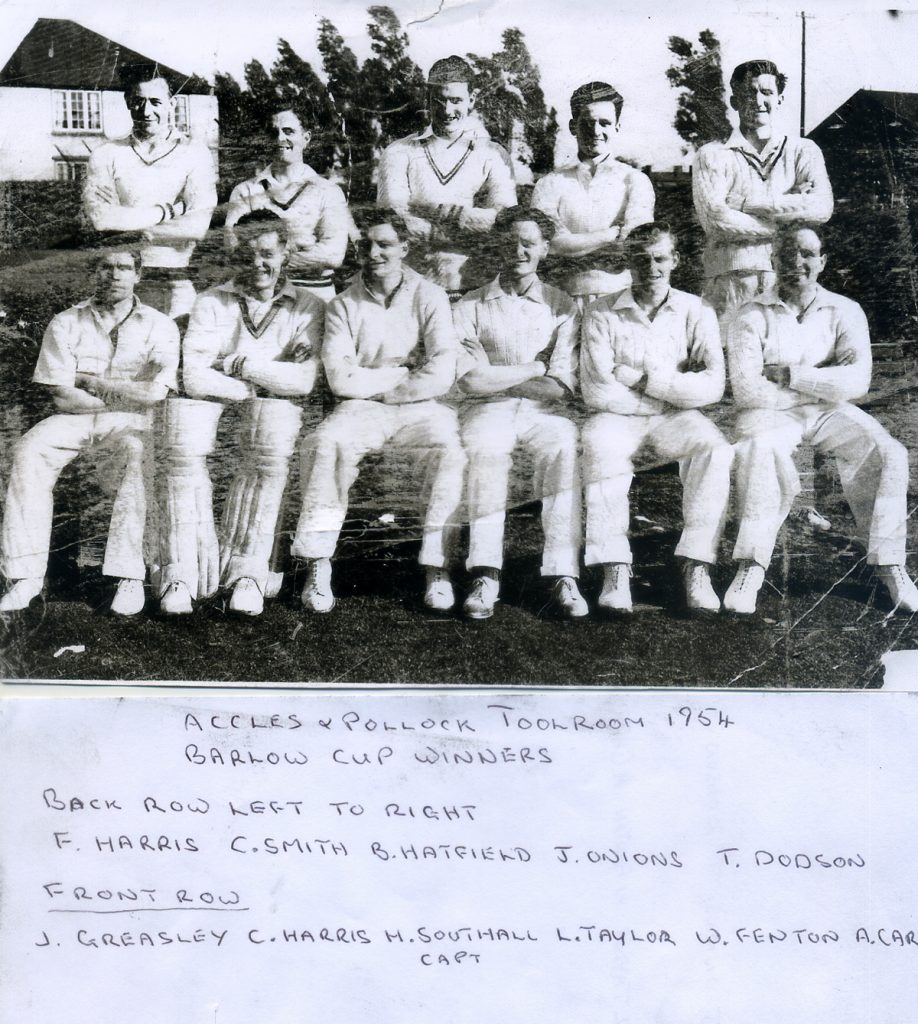

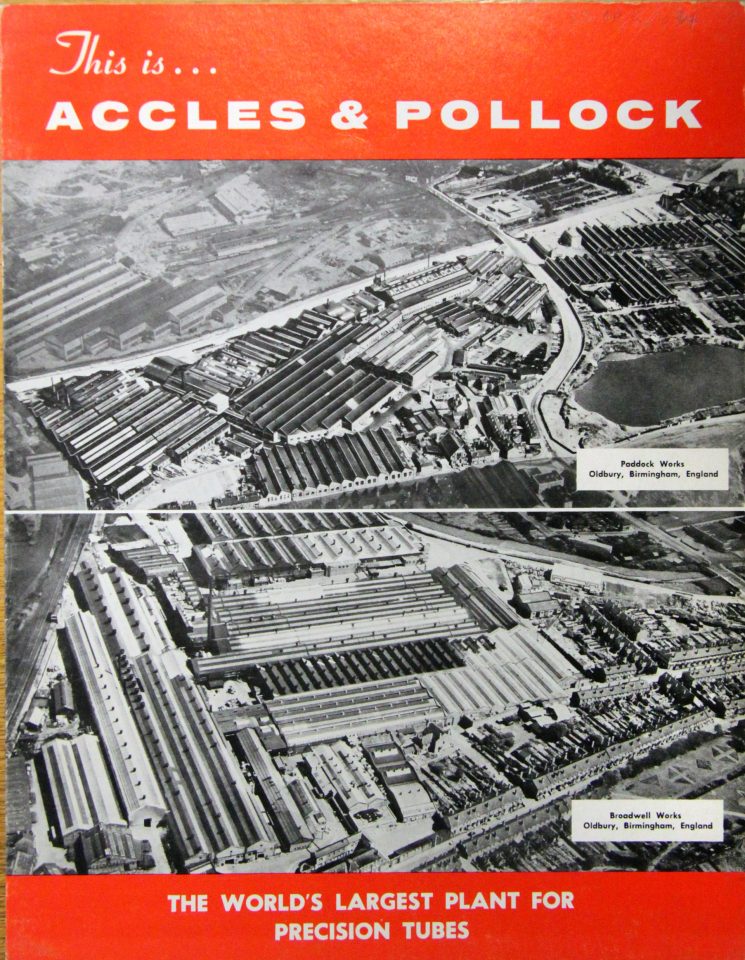

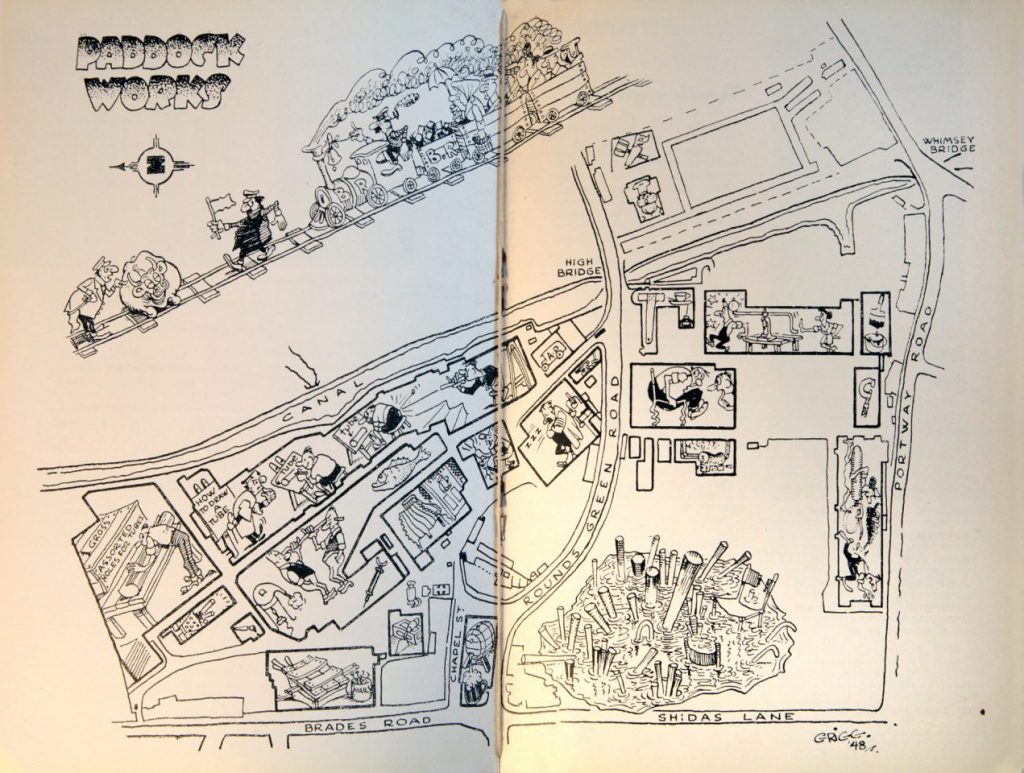

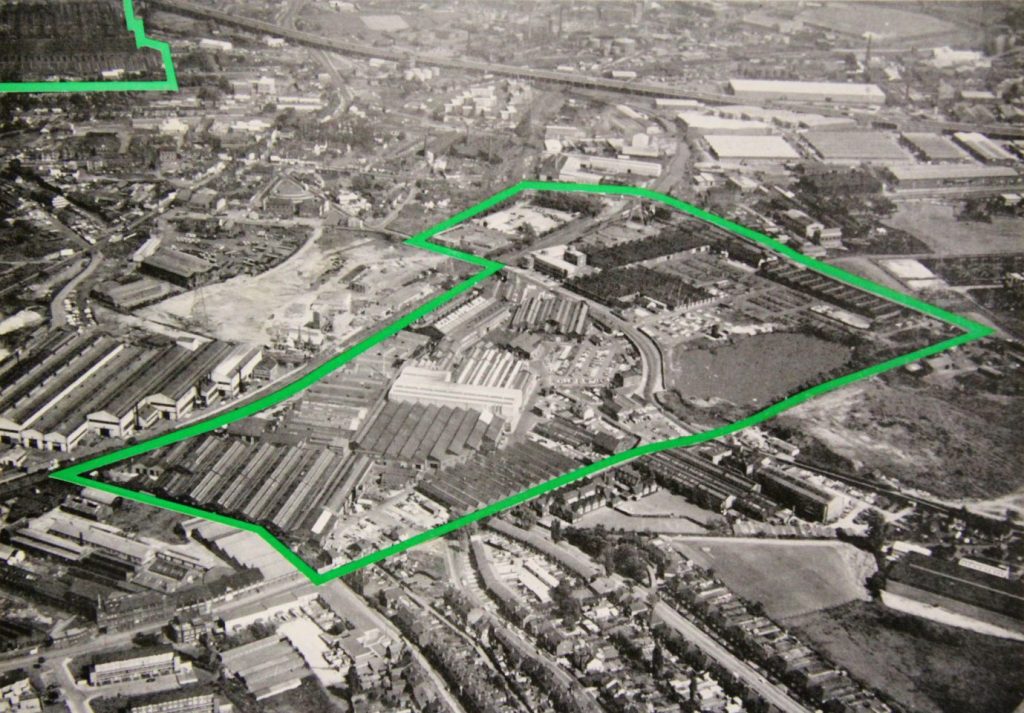

I started work on my 15th birthday at Accles as a trainee Tinsmith. My dad got me a job because he knew the foreman in the tinsmiths, Arthur Holt. My dad worked at Metal Sections, making bus seats in the Broadwell works. He was foreman in the department and my mom worked at the canteen there, which was handy for popping in for a cup of tea. My older brother worked in the Paddock Works tool room, along with two of my uncles, Charles Harris and William Harris (he wife Lillian also worked in the tool room). Another two uncles, Arthur and Albert, worked at the same time in the tube drawing mills. My brother's wife, Joan (nee Clewes) also worked in the offices at A&P. As you can see, it was really a family gathering and a pleasant place to work.

I also attended the A&P day continuation school, which was situated in the Broadwell Works. In 1955, I went in the armed forces at 18, did National Service, then went back and completed an apprenticeship.

There was a guy there called Jack Hipkiss and he taught me everything I knew. I worked there for 15 - 16 years and as a result of what I’d learned, I moved into training youngsters in engineering and sheet metal work. I set up the first youth training scheme in Birmingham, and that was thanks to Accles for teaching me how to do all that kind of stuff.

We started at 7.30 and worked through to 12.30 for lunch, had an hour lunch and finished at half four, five o clock. End of the day they used to queue up at the gates and then they’d go whoosh.

Being on maintenance, say I designed a machine guard and made it in our workshop, then we had to fit it on a weekend. So we used to go in Saturdays and Sundays. Saturdays was a regular thing, all day till four, then on Sundays till lunchtime. We’d go in and fit that machine guard, test it and then it was ready to work the shift on Monday. And we had to fix all the ducting’s in the roofs. We used to do the plating vats for the tubes, we used to build the extractions onto that.

I was really fortunate in knowing about as much as Accles that I did, and it was only because I was working in every department. Someone would phone up; a machine guard had broken down, or a tank needed making for this or some ducting made for that, so the Boss would say, ‘Go on Bryan, measure it up, build it, go back and stick it up.’ Some of the places to work were really dirty and horrible; if we worked on the furnaces, for a start off, we used to have to get down underneath the furnace to look at the extractor ducting. And that was a really filthy dirty job that was. We had some horrible jobs like that; those were the only bits I didn’t like really. The rest of it was all on a par.

You’d not only put the stuff up inside but we’d get up on the roof and fit everything on the top at well. I spent an awful lot of time on the roof. I think I’ve been on every roof at Accles and Pollock, every roof down the Broadwell End, and the PEL. With all the extraction units from the furnaces, you’d build a massive hood over the furnace, some ducting, take it up through the roof, make what they call a roof blade - which was a steel plate with a pipe going through there - and on top of there, you’d put a caul.

The Maintenance Unit was a fair size. A lot of it was hand made stuff. The only power stuff we had was a big guillotine to cut the sheet metal, a folding machine to fold the metal, some steel rollers. All joints and the ducting was done by hand on a bar - you’d make lengths 40 or 50 feet long, pot rivet them together. It was a very interesting job looking back. I was extremely fortunate, not stuck in one place.

It was totally and utterly different. There was no pressure, really, at all. The only pressure was what you put on yourself to get the job done to a proper high standard. The satisfaction was in doing something like that. It was brilliant. I’ve made that.

Accles had their own canteen. They had the lot for their workers. They looked after the youngsters they really did, with all the clubs and activities they put on. They even had a surgery. If you cut your finger they’d got a surgery on site to wrap you up and put you right, it was all laid out very well. I haven’t been to another company that was as efficient and as well run as Accles and Pollock, even now.

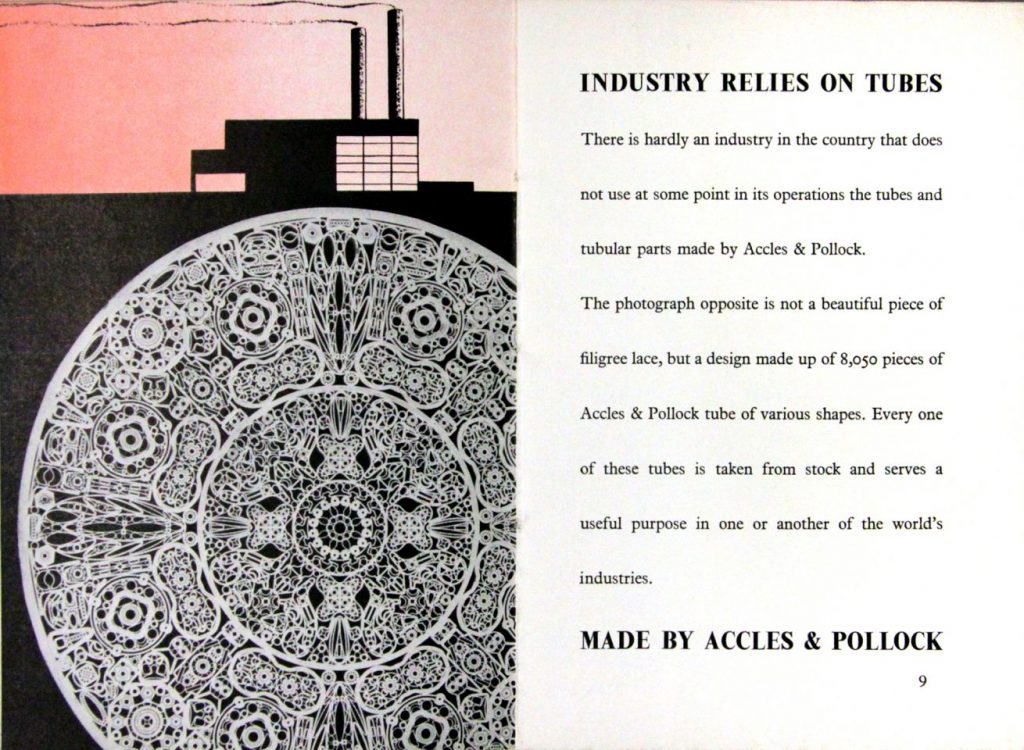

Financially you weren’t well off enough to travel around and socialise and do that kind of thing. I think when I was getting the full wage I was getting £8 a week and that was for seen days. But it was so nice having all the family there; travelling around the different departments, you were talking to one of your relatives in virtually every department. Mary’s sister worked in the fishing rod department, Frankie Vaughn visited while I was there – he was a keen fisherman. You know with fishing rods, well Accles and Pollock were ace at that kind of stuff, doing tapered tubing. It was ideal for doing that kind of stuff.

The transferable skills you got working there were quite amazing. It enabled you to do almost anything really, from making your own cars, all kinds of stuff. I moved to a place in Birmingham making sheet metal filters for John Brown pumping stations all over the world. They sent me to Algiers once to repair something I’d made, which had fallen off the lorry on the way to the site. It all came from Accles and Pollock, it really did. They taught me all that.

Out of all my working life, which finished when I was 65, Accles and Pollock was the best place I ever worked at, even though I worked for myself for a time. It was so friendly and everyone was so helpful and polite you know.”