After the First World War, the British Cyanides Company (now British Industrial Plastics) made thiourea, a chemical compound used to silver-gelatin photographic prints and in the vulcanization of rubber. It also gave weighted silks its rustle, as well strengthening the fabric, and was a core market for the company. As fashions changed and demand fell for taffeta and heavy rustling silks, the company was left with large amounts of thiourea. The company were also facing bankruptcy from a massive fall in cyanide sales. The chief chemist at the firm, Edmund Charles Rossiter came up with the idea of combining thiourea with formaldehyde to produce a new moulding resin, which looked like a watery white syrup. Clear in its pure state, it could be strengthened by cellulose and tinted by numerous pigments to make light, thin, hard, strong, colourful, and translucent articles for the home and kitchen. Its resistance to many chemicals suited it for cosmetics jars and other containers, and its electrical resistance made it desirable for products such as wall outlets and switch plates. The resin set faster, so lower production costs were possible.

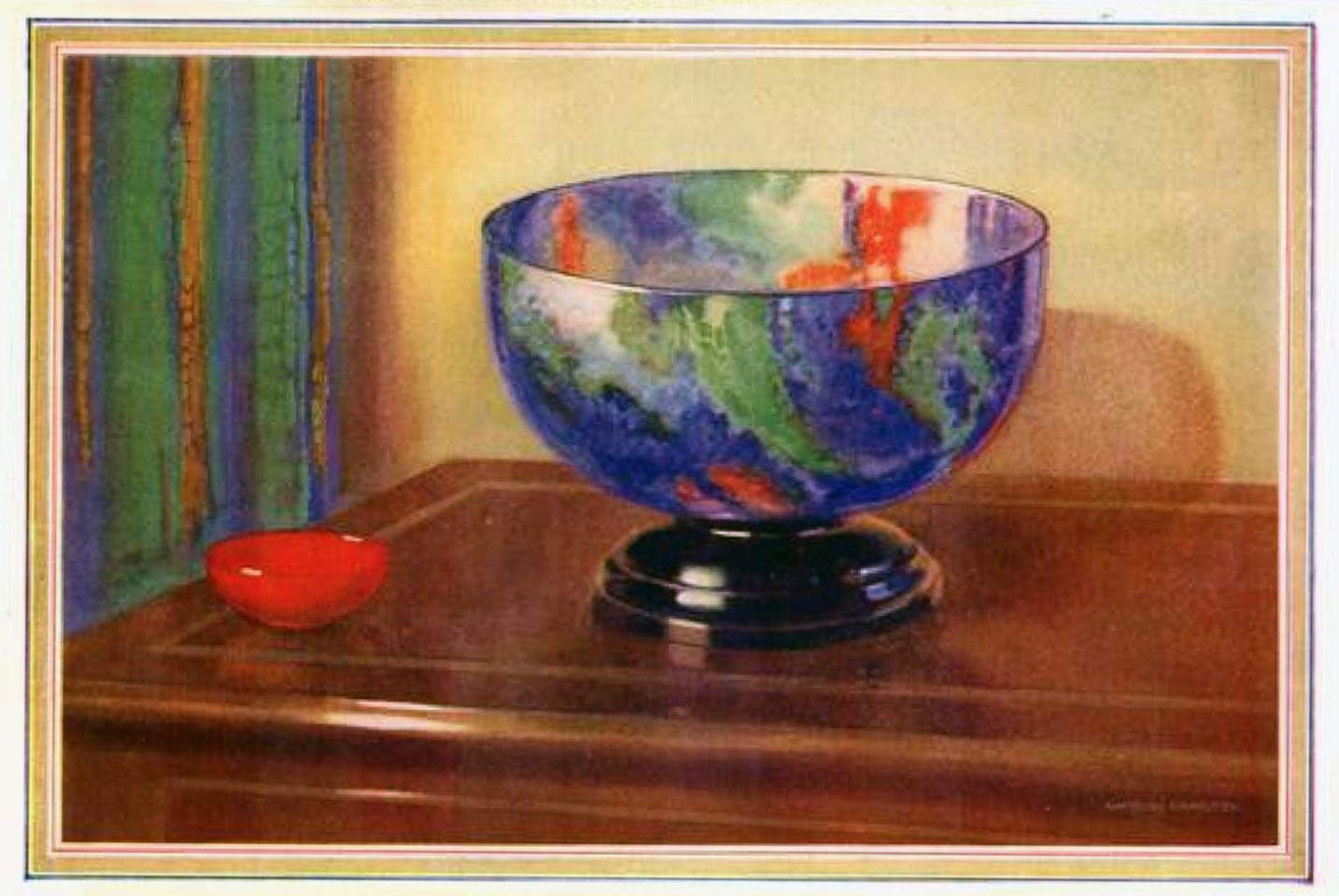

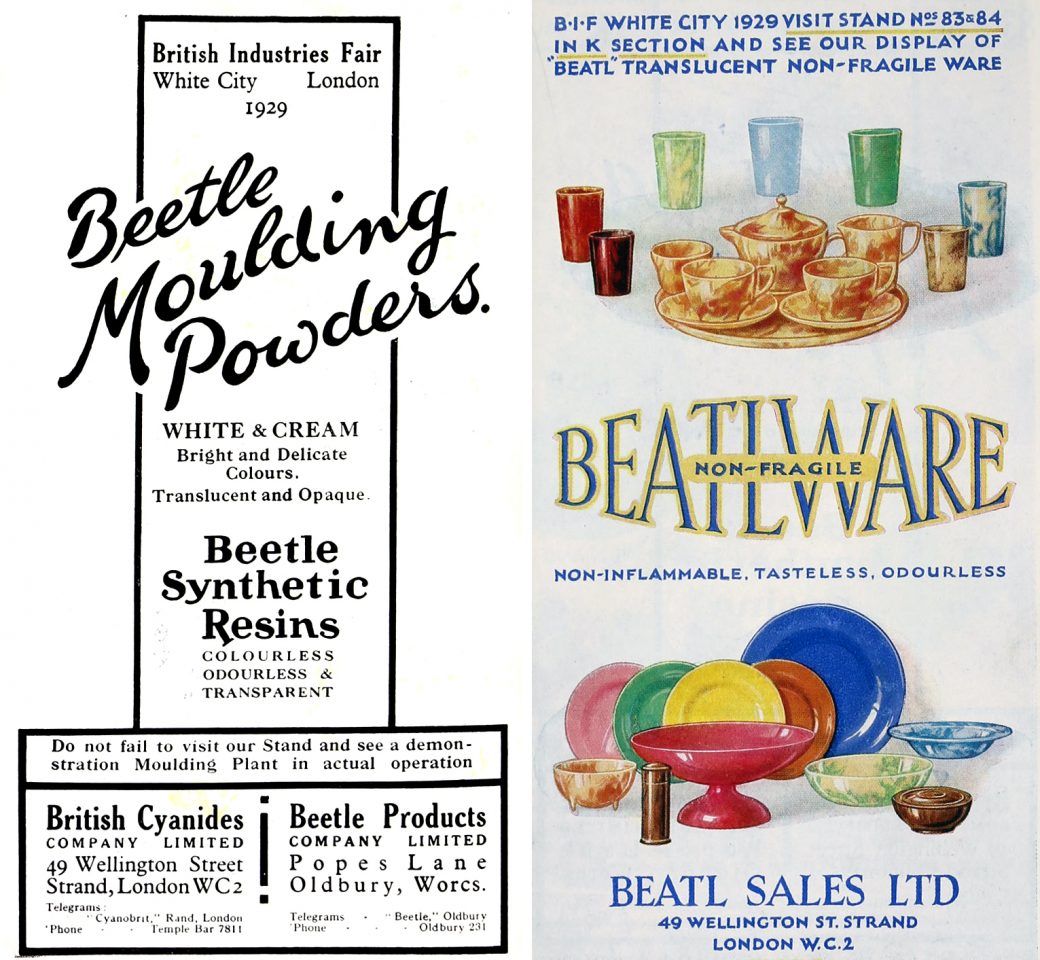

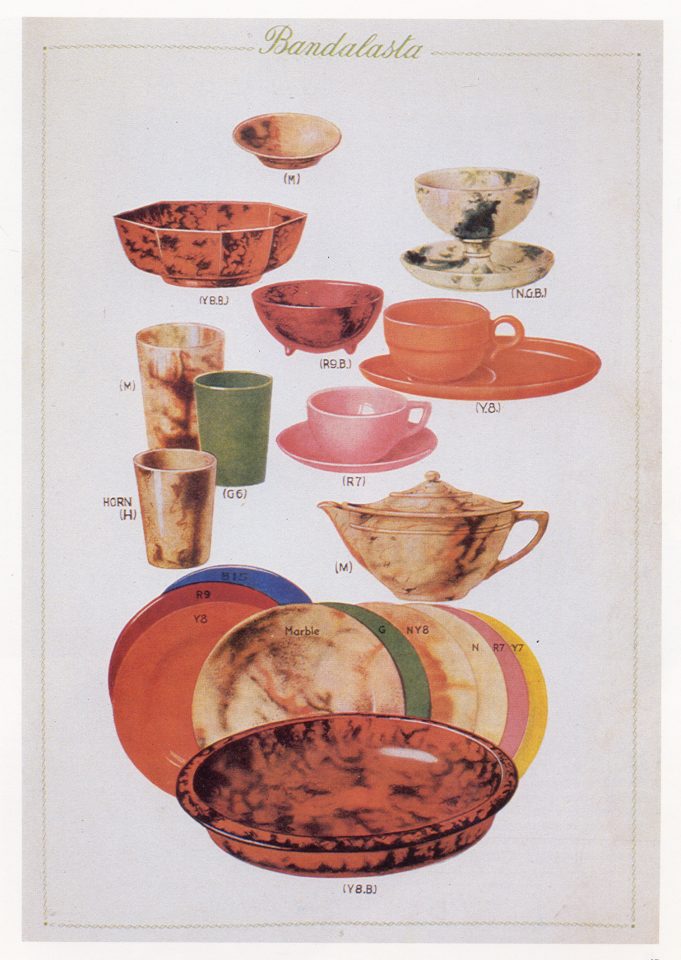

Sample discs moulded from the resin, compounded with slate-dust, chalk, sawdust or other fillers, were shown at the Wembley Exhibition of 1925. They carried the British Cyanides trademark, a beetle. Thus in 1926 the world’s first white commercial moulding powder was produced in Oldbury and the new product went on display to the public at Harrods in London in 1926. The new cups and saucers in a range of colours and marbeled effects were an immediate success. From this pioneering work the famous Banda and Bandalasta trademarks were developed with Brookes and Adams, using as their raw material the Beetle moulding powder.

Within two years Americans in particular were going crazy for these products. Such was the increasing demand that the company purchased its own moulding plant, The Streetly Manufacturing Company Limited in 1929. An article in Women’s Magazine that same year by Leonard Dodds extolled the product:

‘Tea on the lawn amid a garden of gay flowers demands dainty and colourful table-ware. Unfortunately, the fragility of china and glass is a serious drawback, for accidents seem to happen so easily and so often at outdoor meals, and pleasure is

quickly marred when good china is chipped or broken. Now, however, various substitutes are available which combine all the beauty and decorative effect of good china with extreme durability. These wares are admirable for summer meals in the garden or picnic parties, while they are equally suitable for everyday use in the home.’

‘Modern tendencies in decoration need gaily coloured tableware, and the non fragile kinds are made in a galaxy of attractive shades, one of which will be found suitable for all colour schemes, while out-of-doors each design looks so fresh and attractive that it is difficult indeed to choose the best. In self colours the range varies from a fine ivory tone and pale, translucent pastel shades, up to darker and brighter hues. These latter are especially noteworthy for their delicate appearance, which is seldom found in chinaware unless of superlative quality, for bright colourings tend to make even good ware look heavy.

And You Can Get It in Marbled Effects... Some of this ware is also produced in marbled and mottled effects, which have distinctive character and are especially attractive. When the garden is a riot of blossom, nothing looks more inviting than the cunningly mingled colours of this beautiful ware. The finish is equal to that of the best china or glass, and it has the additional advantage of obviating the necessity for constant polishing and cleaning. The new ware is washed in just the same way as china, using warm soapy water. Soda, however, should not be used, as this tends to affect the colours. Any surface stains can be removed easily by rubbing with a little damp salt.’

While noting its value in the nursery for children, and its use as trays, flowers vases and fruit dishes, he finally concluded that ‘The charm and pleasure of tea in the garden is vastly increased by using this new ware, for the haunting fear of broken china is banished for ever.’

In the Story of B.I.P, Cyril S. Dingley, told the story that as the production of Beetle tableware began, it was believed that customers were not too happy about product being associated with the name of an insect; so the name was changed to Beatl, as suggested by a shareholder as contraction of the phrase ‘Beat All’.

At the British Industrial Fair of 1932, an article in the British Plastics and Moulded Products Trader reported: ‘Visitors to the Fair should not fail to see the beautiful Beatl ware which will be exhibited at this stand. These products should be of exceptional interest, as their range is so wide, including all kinds of table-ware, lamps, cigarette boxes, cosmetic containers, picnic outfits, all kinds of fancy goods, trays, as well as door furniture, panels, bathroom and electrical fittings, all made of non-fragile material in the most tasteful and artistic shades.’

At Oldbury, by 1936, the emphasis entirely turned from cyanides to the production of plastics and the company changed its name to British Industrial Plastics (BIP).