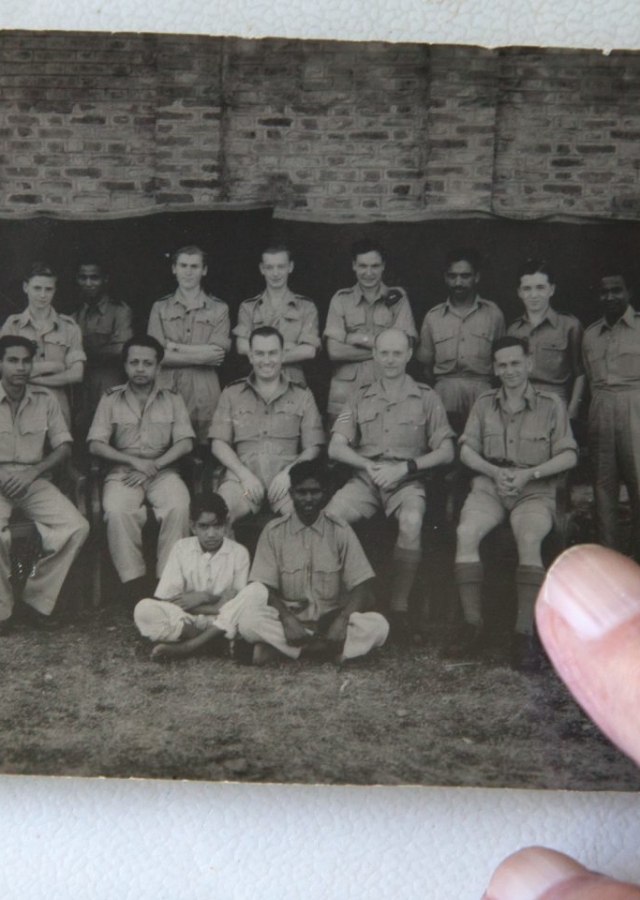

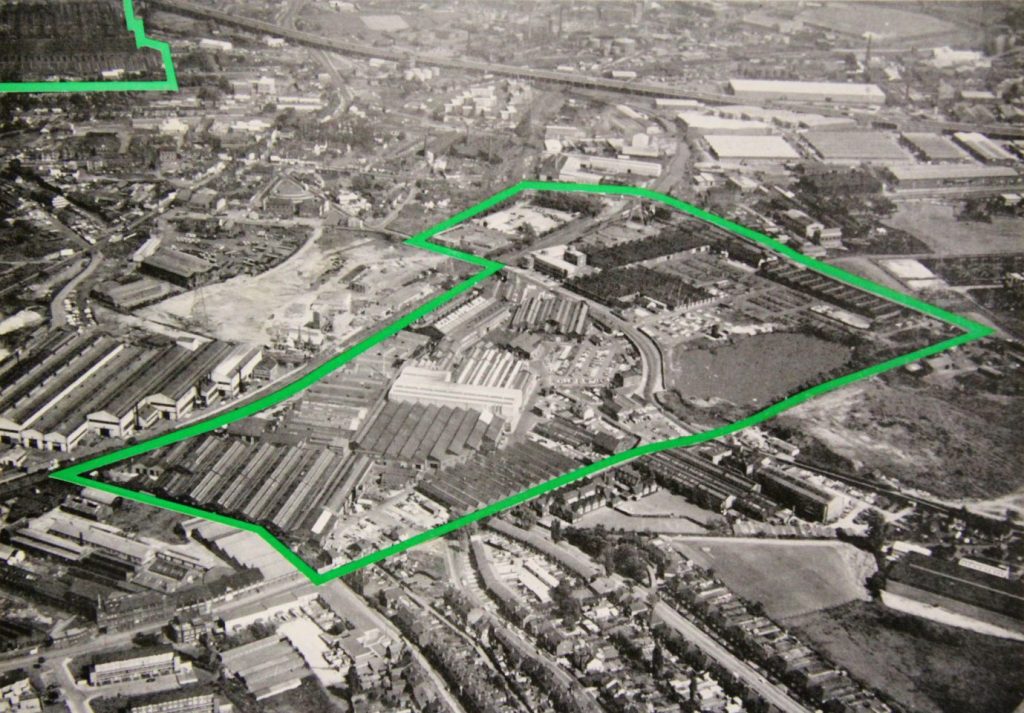

Arthur Guest retired in 1981 after a long career at Accles & Pollock. While at Accles he served in the ARP during the Second World War, but was called up for National Service in India during the post-war period.

“I left school in 1934 and went to work at Accles and Pollock. My dad worked there, but all my brothers worked at the Brades, making gardening tools. First job I had was at the paint shop where they had car frames and they had to be sprayed. Then I had a job in packing. There was a new foreman come and he said to me, ‘You need to get more than that.’ I said, ‘Mate, if you can pack ’em more, bloody pack ’em yourself.’ So he said, ‘Go down and get your bloody cards.’ I said, ‘Fair enough’ and went down for my cards.

The lady supervisor there knew my mother; she said, ‘What you doing down here?’ I explained I’d been given the sack. She got on the phone to him and then said to me, ‘You can go back now.’ I said, ‘I ain’t going back to it.’ She said, ‘Hang on, I’ll see if I can get you another job...’ So she sent me down Broadwell. I said, ‘What will I be doing?‘ ‘Examining,’ she said, ‘That’s what you’ll be doing.’ So that’s how I ended up as an examiner of tubes.

Eventually, I became an Inspector, over a team of six men doing the checking. I had to go over the place, to Bristol Aircraft, to Ford in Dagenham, to Dungeness. When I saw that, that atomic work, it was something. It went down about three miles. I can stand heights, but I couldn’t look down into that. The tubes were controlling the heat. I thought, what would happen if anything went wrong with that, imagine that going wrong? ‘If anything happens they told me, ‘then run like bloody hell.’

There were miles and miles of tunnels under the ground. I ought to have more sense. They put me up in a hotel and the Chief Inspector would come and collect me in a car and we’d drive miles along the sands to get there. There was military all over the place and they kept checking if you had the authority to go down. They took my photo and we had to wait for that and they put it on a badge and gave me a what’s-its-name to check for radiation. I’d never seen anything like that before, it was scary. The best part was when the Chief Inspector said to them, ‘Don’t bother to take my photo, I’m not going down there, but he is.’ He pointed at me.

They found these splits in the tubes, so I had to be the one to go down to check them. I said, ‘What’s caused them to be in this state?’ They were riffy. They were all rusty. It’s stainless steel, I thought, they shouldn’t be like that. It was under the earth, under the sea, so it was puzzling. They said to me, ‘Well, this is the condition they arrive in.’

I told the Chief Inspector that we better to go and have a look at where they were bending the tubes. It was a subsidiary company doing the work in Derby. Then we found out they were treating them all wrong. So then I was going up and down there for six months with the six chaps to check they were redoing it properly. What a palaver that was. But a chauffeur used to pick me up and take me over there. It was the good life.”